Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – Late afternoon in Kuala Lumpur, in the intense heat, Zabi* has just completed his third doctor’s visit in a month, and even though all reports so far are normal, he feels unbearable. I still don't know the cause of my stomach pain.

As a refugee, he doesn't have much money or medical benefits, so he's worried about the cost of seeing a doctor.

When Zabi came to Malaysia from Afghanistan five years ago as a teenager, he had no choice but to protect himself. His family only had enough money for one of them to escape.

“I know it is illegal for refugees to work in Malaysia. But as an orphan, I have no choice as I have no trace of my family at this time. I work about 18 hours a day. But I barely get paid more than 4 ringgit ($0.88) an hour,” the 18-year-old told Al Jazeera.

Zabi works as a housekeeper at a Malaysian-owned hotel in Kuala Lumpur, but does not have a written contract because she is a refugee and is not officially allowed to work.

He holds a series of other jobs, including as a security guard, in a restaurant, and in customer service, and is struggling to make enough money to pay his monthly rent of 500 Malaysian ringgit ($106). I am living a happy life.

“I eat Maggi instant noodles almost every day after a very tiring and long working day,” he said.

Malaysia does not have a formal framework for refugees. That means they are left in a legal no-man's land, at risk of exploitation by those who employ them. Under Malaysian law, refugees are no different from illegal immigrants, who are often subject to government crackdowns.

Asked about refugees at the United Nations last month, Malaysia's representative defended the government's approach and said there was no room for change.

“Who qualifies as a refugee? Who qualifies as an asylum seeker? Who are economic migrants? Who determines them as such?” Foreign Affairs, according to Malay Mail. Bala Chandran Sarman, Deputy Secretary-General (Multilateral Affairs) of the Ministry, spoke at the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in Geneva.

lack of legal protection

Although Malaysia is a member of the United Nations, it has never signed the 1951 Refugee Convention and has no legislation (PDF) to recognize and serve people fleeing persecution or conflict.

Refugees also have no right to work, go to school, or receive medical care.

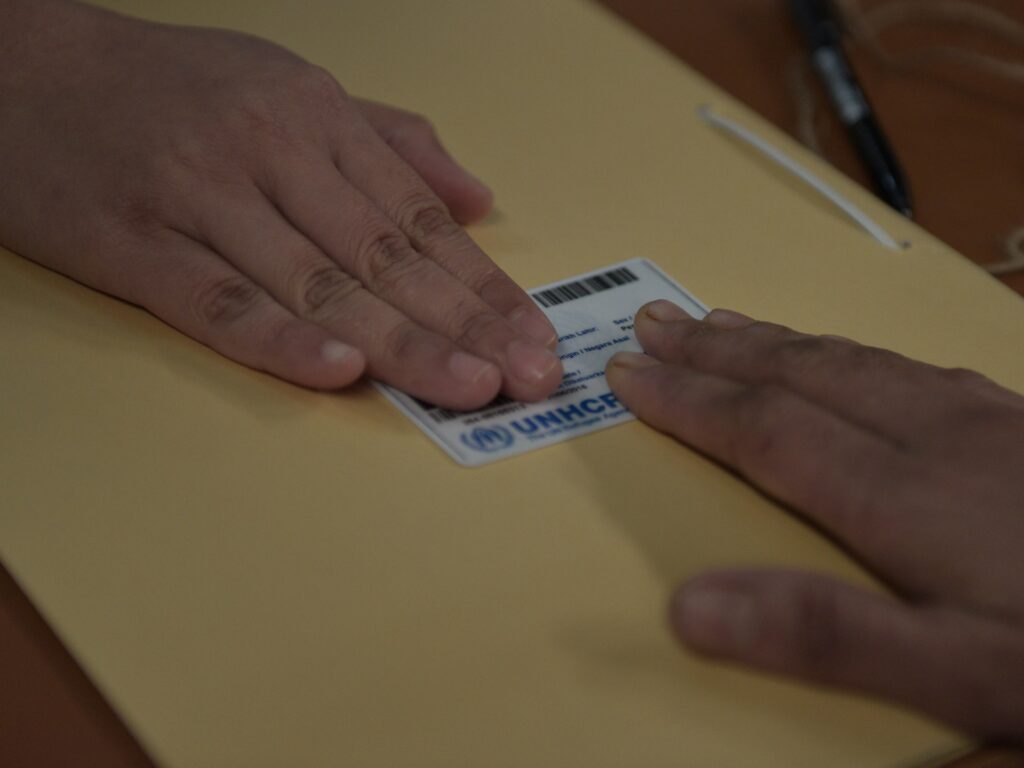

Registering with a field office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provides a degree of protection and assistance, including limited access to health care, education, and other services provided by the United Nations and its partners. .

“This is just an identification card and has no formal legal value in Malaysia,” UNHCR's website says of the card given to everyone registered on it.

The Malaysian government has announced that in 2022 all asylum seekers and refugees will be required to register with the government's Refugee Tracking Information System (TRIS), which was launched in 2017.

The TRIS website mentions the risks of security and social issues related to the influx of refugees, but registration could also allow cardholders to work in some, mostly unskilled, sectors. It suggests that there is.

“Due to lack of legal protection, refugees are forced to work illegally, and most of the jobs they find are 3D jobs, the ‘difficult, dangerous and dirty’ types of jobs that Malaysians seek to avoid. “, said co-researcher Jana Stanfield. She is the founder of Together We Can Change the World and the founder of Refugee Film School in Kuala Lumpur.

Without legal protection and proper contracts, many do not receive Malaysia's national minimum wage of 1,500 Malaysian ringgit ($329) per month or 7.21 Malaysian ringgit ($1.64) per hour (introduced in May 2022).

Zabi, who studied English for five months after coming to Malaysia in 2018, said his boss at the security company he used to work for agreed to pay him about 1,000 Malaysian ringgit ($219) a month, but never paid him. says.

Even now, he is forced to work unpaid overtime and other roles to meet his employer's needs. He told Al Jazeera that he had no other choice and had to agree to these terms.

“Win-win”

Of the 185,000 refugees registered with refugee agencies in Malaysia, more than 70 per cent are of working age. According to information gathered from refugee communities, most refugees make a living in restaurants, retail stores, and other service industries, as well as agriculture and construction.

UNHCR Spokesperson Yanteh Ismail said: “This is a 'win-win' for Malaysia as it takes into account both the humanitarian needs of refugees while also benefiting the Malaysian economy as it recovers from the social and economic impact of the pandemic.”・It's a win.'' In a statement to Al Jazeera, he spoke about allowing the community to operate legally.

Malaysia has in the past allowed certain refugee groups to join the workforce.

In 2015, some Syrians were allowed to work and send their children to school under a system built on early 1990s initiatives for Bosnians fleeing war in the Balkans.

“Malaysia can allow refugees to exercise their right to work under the existing legal framework…and expand this to include education and healthcare,” says Malaysia-based investigative film said creator and activist Mahi Ramakrishnan. “The question is whether the government has the political will to do so.”

In a 2017 pilot project, around 300 Rohingya refugees with UNHCR cards were allowed to work legally on plantations and in the manufacturing sector, but were not recruited.

The Ministry of Human Resources said in October that refugees could be formally allowed to work in so-called “3D jobs” amid a shortage of workers who are usually brought in through government-backed arrangements from countries such as Bangladesh and Indonesia. It was announced that there is. These systems are currently under review as the Malaysian government seeks to regularize its policies towards foreign workers.

Ultimately, refugee advocates say governments need to take the lead on policy changes.

“Giving refugees the right to work means ensuring that they can earn a safe, decent and dignified living,” Hui Yin Tam, executive director of Asylum Access, told Al Jazeera. Told. He said that implementing this “requires a multifaceted approach led by governments, in consultation with refugee communities, changing laws, policies and attitudes, and building frameworks that recognize and support refugee rights and potential.” '', he emphasized.

Tam added that, like the rest of the workforce, the skills and experience of individual refugees need to be valued in the workplace.

Abol Fazli*, an Afghan refugee schoolteacher whose village was burned down by the Taliban, agreed.

“We had a life to live until we were evacuated to another land,” he said. “We are educated and resourceful. Host countries like Malaysia will utilize us not only in agriculture but also in socio-economic development,” said the J.D. Ph.D. said the 28-year-old, who is working on.

Although UNHCR remains hopeful that a resolution will eventually be reached, the latest comments in the UPR suggest that it may not happen soon.

For refugees like Zabi, that means an ongoing struggle.

“I want to go to university. I love learning new languages,” he told Al Jazeera. “My life now is just eating, sleeping and working. I have no plans for the future because I know that none of my plans will work out. But I will keep trying as always.”

*Pseudonyms used to protect refugee identities