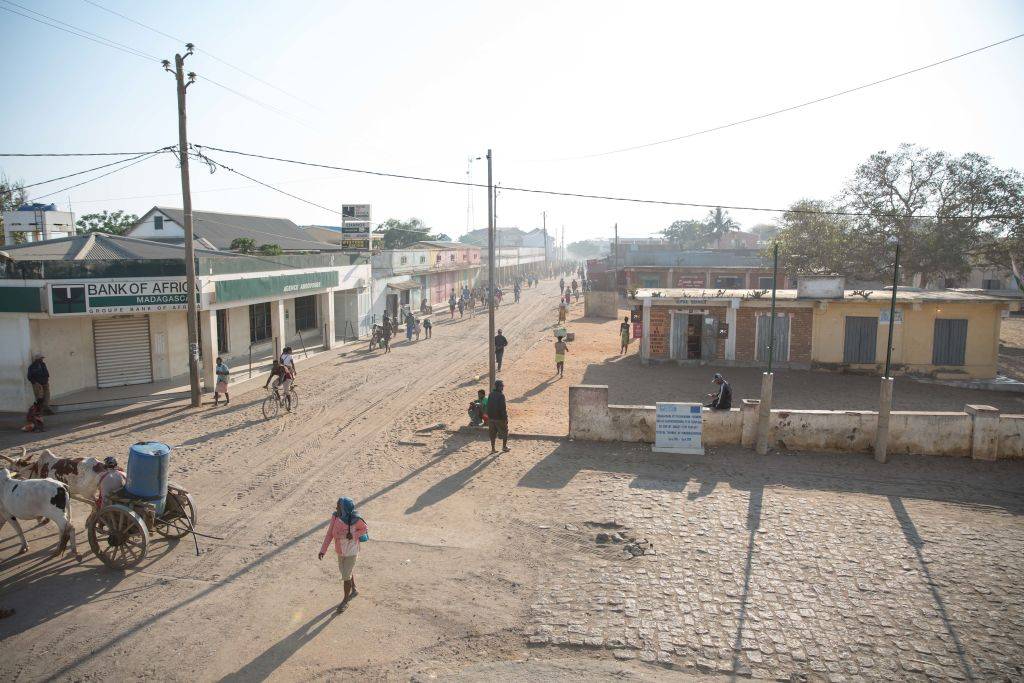

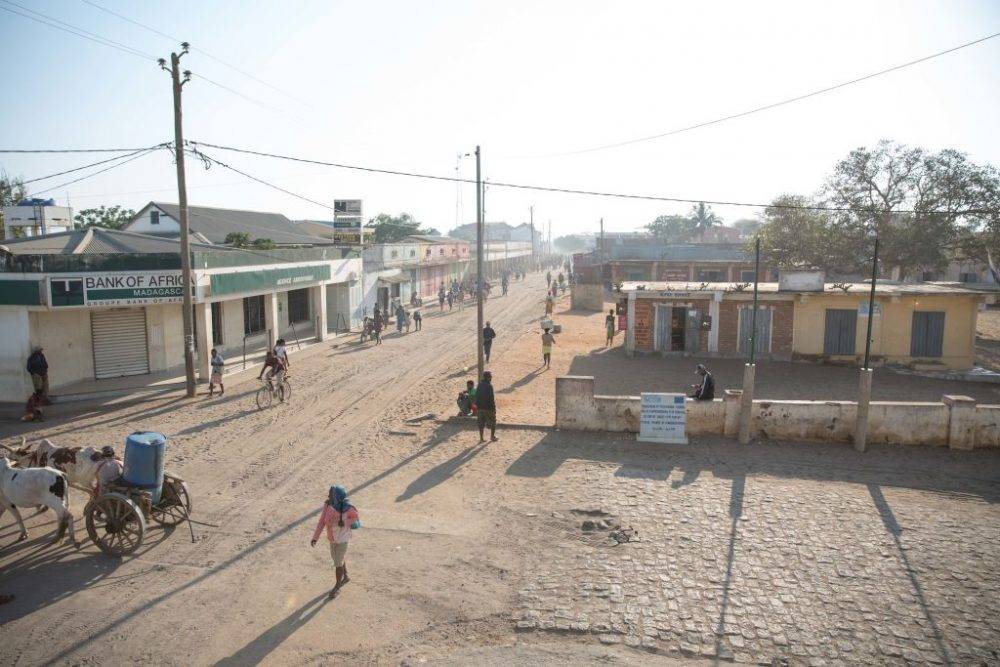

Locals walk through Ambobombe, a city in the Androi region of southern Madagascar. (Photo by: Sally Hayden/SOPA Images/LightRocket, Getty Images)

IIn a small village in southern Madagascar, dozens of women take shelter from the scorching sun under a tree, waiting to have their children weighed. The country has seen a decline in rainfall since October, raising concerns that hunger could worsen as the El Niño weather pattern takes hold.

The country is particularly exposed to extreme weather events such as storms and droughts, which scientists say are expected to worsen due to climate change.

“Madagascar is currently facing a climate crisis,” said Lina Gelani, UN Climate Crisis Coordinator for El Niño.

At least 1.3 million people in Madagascar, one of the world's poorest countries, already suffer from malnutrition, according to the United Nations. In recent years, large swaths of the south have been experiencing the worst drought in 40 years. Weather forecasts predict an even drier 2024, with potentially dire consequences for the harvest season, which begins in May.

“Nothing is growing on our land. Everything we plant ends up falling down. It is because of all this that we are suffering,” Nasoro said. She came to the Manindra village community center with her other mothers to get their children tested.

A dry wind blows across the red earth, and the temperature is around 35 degrees.

“I come every two weeks to weigh myself and check on my health,” said Alisoa, who walked 7 kilometers to put her 1-year-old son on the scale.

Three months ago, she noticed that the boy was acutely malnourished. She is currently monitoring his muscle mass with a bracelet.

“We should give him fish and bananas and pineapples. But we don't have enough means or enough food. It's not raining,” she said.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2023 was the warmest year on record worldwide. The association warned last month that this year could be even hotter, as the naturally occurring El Niño weather pattern often causes global temperatures to rise.

Gerani, who toured Madagascar last week, said early warning systems that detect climate risks are key to quickly delivering aid such as seeds, food and finance.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is trying to help farmers. Some companies are using a phone app developed by the company to compile agro-weather data.

“It helps us predict rainfall and wind more accurately and decide whether to plant or not,” said Bienvenue Manasoa, who grows corn, sorghum and peanuts. “It changed our lives.”

Some people have started planting more drought-resistant seeds.

“We decided to grow millet because it is highly nutritious and does not require a lot of water to grow,” said Iari Tshivonanonby, who sells seeds to FAO. —AFP