Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam – On a sunny afternoon in California in late September, Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Trinh toured Silicon Valley in a friendly atmosphere with representatives from semiconductor companies Synopsys and Nvidia.

A little more than a month ago in Hanoi, Mr. Pham ordered four government ministries to increase the number of Vietnamese engineers available to work on semiconductor production by tens of thousands.

Government efforts to make Vietnam an attractive option for chip investment continue in the new year.

Science and Technology Minister Huynh Thanh Dat told local media last month that authorities were offering tax incentives for high value-added products such as semiconductors.

Dutt said the country wants to welcome a “wave” of investment by working with other ministries and high-tech companies to boost research and attract talent to the semiconductor sector.

Vietnam aims to become a leading player in the global supply chain for semiconductors (wafer-thin integrated circuits), which are essential to modern technology.

As geopolitical tensions rise and Hanoi and many countries agree on the need to avoid risks from China, the Southeast Asian nation is seeking to counter the dominance of Taiwan and South Korea. It seems like momentum is on their side.

But Vietnam also faces obstacles such as a lack of skilled labor and energy insecurity in its northern technology manufacturing hub.

The global push to diversify semiconductor supply chains is in line with Hanoi's development goals, said senior researcher at the Singapore-based ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and former Vietnam Ministry of Foreign Affairs official. said Le Hong Hiep.

“The semiconductor industry is considered a very important industry that can support Vietnam's economic transformation and turn Vietnam into a developed high-income economy by 2045,” Hiep told Al Jazeera.

“From the perspective of timing and strategic setting, it is advantageous for Vietnam to develop the industry now.”

On the surface, Vietnam's chip ambitions appear to be thriving amid an influx of foreign capital.

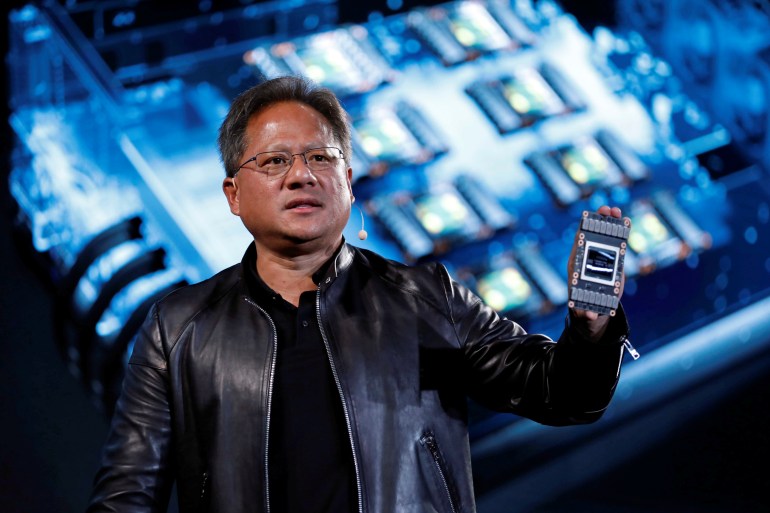

According to local media reports, Nvidia co-founder and CEO Jensen Huang, who visited Hanoi in early December, called Vietnam the semiconductor giant's “second home” and said that he The company has pledged to expand its partnerships with companies and establish bases in the country.

Nvidia, whose market capitalization exceeded $2 trillion last week, said it had invested $12 million in the country so far.

An Nvidia spokesperson declined to comment on Nvidia's future operations in Vietnam when contacted by Al Jazeera.

Vietnam has about 5,000 semiconductor-trained engineers and will need up to 20,000 over the next five years, according to the U.S.-ASEAN Economic Council.

“When companies look at Vietnam, it looks very good on the surface, but when you actually go and see if there is enough electricity, what the infrastructure is like, and most importantly “I don't think we need to look at what the human resources are like in the future. I don't think Vietnam will become the kind of manufacturing country that they think they are,” said a professor at the National Military University in Washington, D.C., who specializes in Southeast Asia. Professor Zachary Abuza told Al Jazeera.

Nguyen Thanh Yen, chief engineer at the Hanoi branch of South Korean chip design company CoAsia SEMI, said Vietnamese authorities are aware of the labor shortage and are leading efforts to train more engineers. .

“The government is currently actively planning a dedicated program to increase the number of semiconductor engineers,” Yen told Al Jazeera.

Semiconductors are the centerpiece of a historic rapprochement between Vietnam and the United States announced in September, when the two countries agreed to a comprehensive strategic partnership at the top of Hanoi's diplomatic hierarchy.

“We will deepen our cooperation on critical and emerging technologies, especially building more resilient semiconductor supply chains,” U.S. President Joe Biden said in a joint press conference with Nguyen Phu Trong, general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam, on September 9. “There is,” he said. .

U.S. semiconductor companies appear to be aligned with Washington's policies.

Arizona-based Amkor began operating a $1.6 billion chip factory in northern Vietnam in October, and Delaware-based Marvell announced in May that it would establish a semiconductor design center in the country.

Korean companies are also getting into this. Samsung, Vietnam's largest investor, announced in August 2022 that it would invest $3.3 billion to manufacture semiconductor components in the country.

Hanami Micronbina, which specializes in chip packaging and memory products, is building a second factory in Vietnam and plans to invest $1 billion in the country by 2025, Nikkei Asia reported.

Abuza said semiconductor companies are “competing for this very small, tight labor market.” “[Vietnam] To achieve this, we would need to increase the proportion of engineers by about five times each year. ”

Other countries, such as the Yen, are optimistic about Vietnam's ability to meet this challenge.

He said the country excels in mathematics and science, and 20 polytechnics are launching semiconductor training programs with the goal of adding 50,000 engineers to the workforce by 2030.

“Vietnam has the advantage of young and hungry talent,” Yen said. “The fields that help them make money the easiest are usually the technology fields. Semiconductors are hot right now.”

Help also comes from outside.

During his visit to Vietnam, Biden announced $2 million in seed funding for training in the country's semiconductor industry.

Bruno Sivanandan, co-chair of the Vietnam European Chamber of Commerce's Digital Sector Committee, said Europe could be involved next.

“There is a possibility of partnering with European academies to support the education of Vietnamese workers,” Sivanandan told Al Jazeera. “Major companies are paying attention to Vietnam because it has huge unrealized potential.”

Still, Vietnam may not be able to afford access to regional challengers vying for investment.

Mr Hiep of ISEAS said Malaysia and Singapore were formidable competitors, with Indonesia and Thailand also chasing the sector.

“Everyone is looking for opportunities to establish a presence in the global chip supply chain,” Hiep said. “It's a very competitive industry.”

Energy insecurity is also an issue.

Last year, northern regions experienced intermittent power outages during Vietnam's hottest summer ever. In early June, during a power outage in Hanoi, the weather was so hot that some families took refuge in caves in the mountains near the city center.

For weeks, factories in an industrial park in northern Vietnam were plunged into darkness for hours in the afternoon.

“We had to shut down operations because there was no energy for about four or five hours during the day,” a Ho Chi Minh City-based individual working in the energy sector told Al Jazeera. He was not authorized by the company to discuss the topic.

“Samsung and other Korean factories were in a major crisis as they had to shut down their factories completely due to power shortages.”

After the power outage, authorities launched an investigation into state-owned power company EVN. Authorities ultimately disciplined 161 EVN employees for the lack of electricity.

Northern Vietnam relies heavily on hydroelectric dams, which can run dry during the hottest months of the year when demand is highest. The infrastructure is outdated and the country “lacks the grid capacity and power resources to deal with the problem,” an energy sector employee said.

“We should have invested in transmission and power resources in northern Vietnam years ago, but EVN has fallen behind,” he said.

“In northern Vietnam, [factories] We will face major challenges regarding energy security. ”

Energy is also a concern for European investment.

Under the terms of the European Union's trade deal with Vietnam, European companies doing business with the country will have to comply with increasingly strict regulations on carbon emissions, creating problems as long as Vietnam relies heavily on coal. there is a possibility.

“To do business with Europe, we have to meet these requirements on carbon emissions,” Sivanandan said. “If you apply this to the semiconductor industry, this is going to be a barrier.”

Abuza said there is a significant gap between Vietnam's potential and the reality on the ground.

“These chip factories and server farms and all the high-tech businesses that Vietnam wants to do are actually dependent on very reliable electricity, and they don't have it,” he said. Told. “Vietnam has great potential for investors, but there are many issues that are difficult to resolve.”