- The latest Ritshidze report lays bare once again the abuse and humiliation some people experience in public health facilities.

- A cursory assessment found some of the report‘s findings are worse than those recorded in 2021 and 2022.

- Spotlight speaks to public healthcare experts about possible solutions to challenges facing marginalised groups.

Many people at high risk of contracting HIV or already living with HIV continue to face uncaring, disrespectful, cruel, and even abusive treatment when visiting clinics and community healthcare centres, according to the third edition of the Ritshidze State of Healthcare for Key Populations report.

The report also found because of discrimination and privacy violations, some people stop taking their treatment or leave the clinics without the services they need.

Key populations – including sex workers, gay men, transgender people, people who inject drugs and prisoners – accounted for 70% of new HIV infections around the world in 2021, according to the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

According to South Africa’s fifth National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2023-2028, key populations have the highest prevalence and incidence of HIV in the country for multiple reasons, including inadequate efforts to reach these people, stigma, and discrimination.

HIV prevalence in female sex workers was at around 59% in South Africa in 2022 and at 30% in men who have sex with men, according to the most recent estimates from Thembisa, the leading mathematical model of HIV in South Africa.

“In our clinics we are frequently laughed at & judged. It forces some people to stop going entirely. Our clinics must treat people who use drugs, sex workers, & the LGBTQIA community with dignity & respect, so that we can protect our own health & lives” #KeyPopsHealth pic.twitter.com/uX3viMM9F3

— Ritshidze (@RitshidzeSA) February 29, 2024

For this year’s Ritshidze report, 13 832 people were surveyed, which include 2 612 gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), 6 097 people who use drugs (PWUD), 3 700 sex workers, and 1 423 transgender people.

The data shows 75% of people in key populations use public clinics.

Few people said facility staff were nice to them and privacy violations are extremely common.

A cursory Spotlight assessment found some of Ritshidze’s latest findings are worse than those they recorded in 2021 and 2022.

Though such year-on-year comparisons should not be overinterpreted – the survey sample and some survey questions changed year on year and Ritshidze does not conduct all the statistical analysis one would see in academic publications – the picture is nevertheless a grim one and based on real-world reporting by affected people and thus worth taking seriously.

Ritshidze is a community-led clinic monitoring project implemented by several organisations representing people living with HIV, including the Treatment Action Campaign and National Association of People Living with HIV.

Access to health services

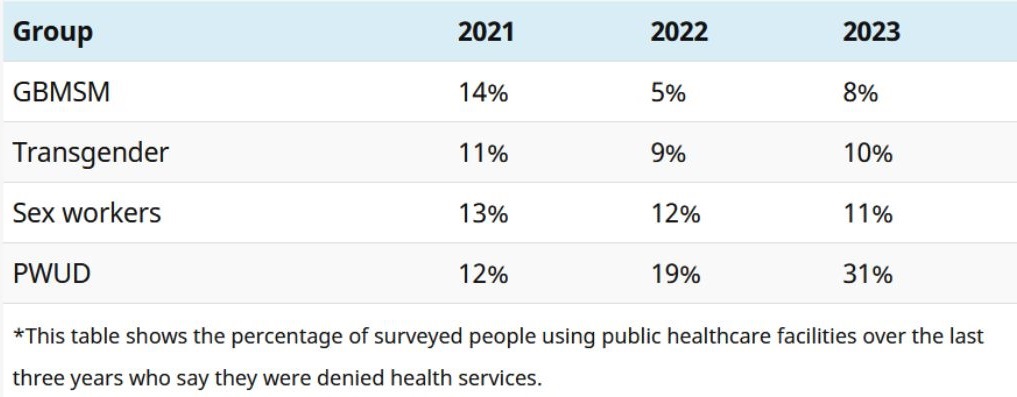

Regarding members of key populations being denied access to healthcare, the Ritshidze data generally does not show any clear trends over the last three years – although their reports provide compelling evidence that some people, probably in the region of 10% of people belonging to key populations, are being denied service.

The one group of people for who things appear to have gotten worse over the last three years is people who use drugs.

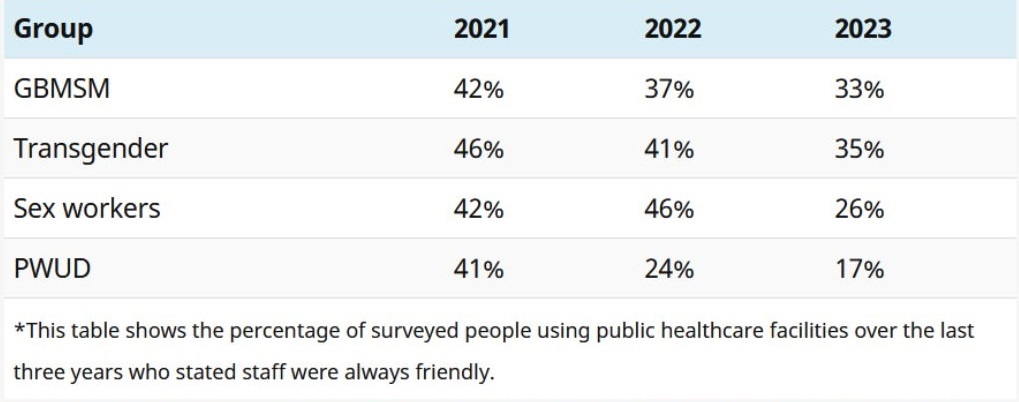

Friendly services dip

Over the last three reports, indicators of friendliness and professionalism at facilities have been trending in the wrong direction.

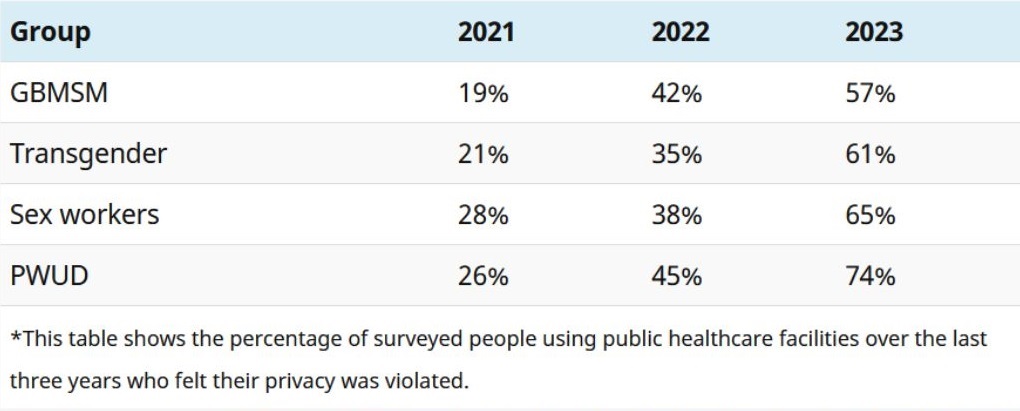

Privacy violations getting worse

Looking at Ritshidze’s figures for the last three years, there appears to be a clear trend of privacy violations getting worse.

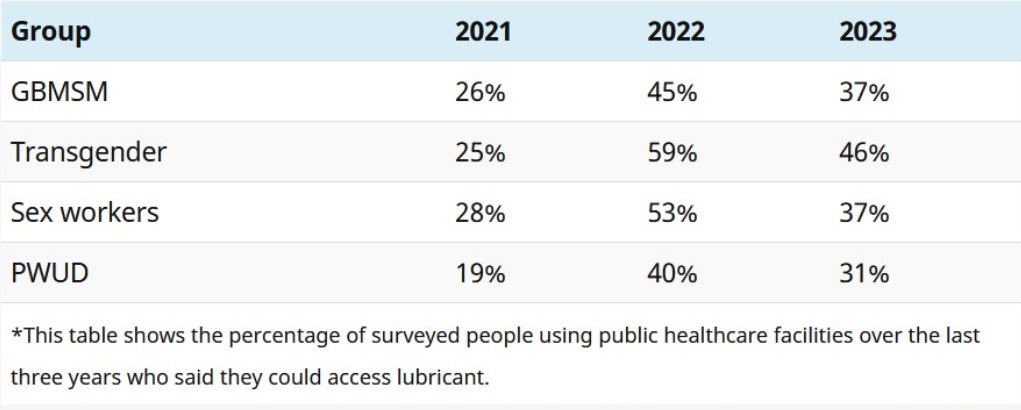

As shown in the below table, the percentage of people who did not think their privacy was well respected at the facility has been increasing year on year for all four key population groups.

Peer-led support

One way to ensure better access to public health services for key population groups is for these services to be run by people from these groups, says Jacqueline Pienaar, a psychologist and public health specialist and technical director at The Aurum Institute (an NGO).

“One of the core success factors of NGO-led facilities is that they are peer-led, which means that if it is a clinic for sex workers it is run by sex workers, if it is a clinic for men sleeping with men it is led by men sleeping with men.

“This allows the clinic to know what the health needs and sensitivities are of that particular group, which creates a more welcoming and safe space.”

READ | PrEP pills are available in SA – but barriers are hindering uptake

Pienaar says another success factor of NGO-led clinics is they have community advisory boards made up of key population groups who recommend how services should be rolled out or provided where they are needed most.

“So, it is not a top-down approach where a particular institute decides how services are going to be provided but a collaborative, co-creation process with the community we serve where the community advisory board serves as the liaison and provides the input as to what services are needed and why people are not coming up for treatment.”

‘Understanding who you are working with’

Pienaar says some nurses at government clinics are not sensitised and understanding that there is diversity in sexual orientation and how people appear.

“When nurses are confronted with people that do not fit a particular social mould, they act out and they do not understand that it is actually hurtful when you call your colleagues to come out and see a transwoman or it is hurtful if you do not accept that the person you are seeing is a sex worker because sex work is also a form of work,” she adds.

Sensitisation at Centres of Excellence

Through the US President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (PEPFAR) funded Centres of Excellence – these are selected public clinics designated to provide specialised services for key populations – around 200 public clinics will be targeted this year to improve access to healthcare services for key populations.

The sensitisation work involves training healthcare workers at public clinics to understand the sexual orientation spectrum of key populations.

One way of ending discrimination, Pienaar says, is greater exposure of public clinic nurses to key populations through creating key population-friendly centres.

“Sometimes the nurses are not wilfully trying [to] be nasty. They have just not been exposed to working with key populations, so it is foreign to them when a transgender woman walks in. They do not know what services to offer or what to ask them,” says Pienaar.

Ritshidze senior researcher James Oladipo believes these Centres of Excellence could be a workable solution.

However, they will require additional staffing and nurses at these clinics will need to be extensively trained to deal with the complex health needs of key populations.

“Centres of Excellence have been identified among existing clinics to provide services to key populations.

“However, they will only be workable if they are friendly, safe, and provide confidential spaces; otherwise, key populations will not use them.

“These clinics will need people with the necessary expertise key populations need in order to support and instil culture change within the facility,” says Oladipo.

Access to PrEP

Ritshidze states people in key populations are likely not to reveal their sexual orientation at a clinic because of the ill-treatment they could face, and this can make it difficult to offer PrEP to those people.

PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, refers to antiretrovirals taken to prevent HIV infection.

Ritshidze argues information campaigns such as putting up posters and daily talks about PrEP could help to raise more awareness.

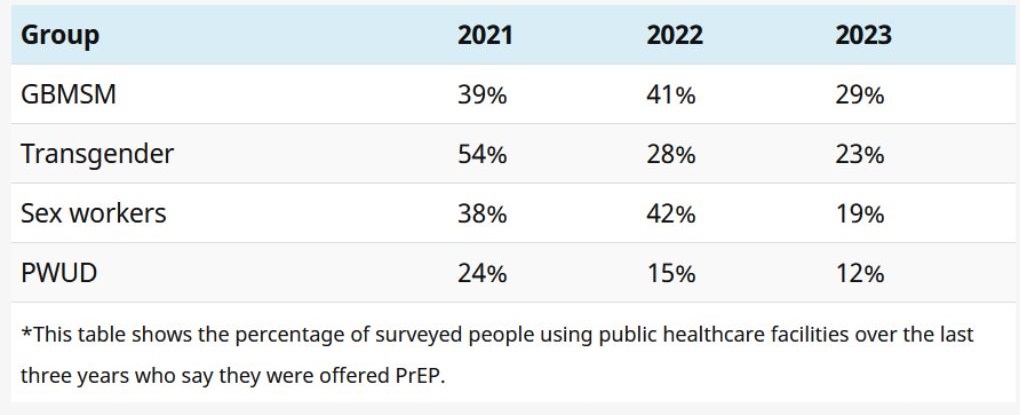

While there has been an ongoing increase in the number of sites where staff say they prioritise offering PrEP to key populations, a less rosy picture emerged when Ritshidze asked members of key populations whether they’ve been offered PrEP.

Looking at the figures for the last three years in totality, the general trend reported by members of key populations is downward.

Access to lubricants

According to the report, gaps lie in many services and not only PrEP availability. While most facilities had male condoms easily available for people to take, lubricants were much harder to find.

When Spotlight visited Bodibe New Clinic – a site monitored by Ritshidze in the North West – the male condom dispensers were full, and they had enough anti-retroviral treatment in stock.

However, a senior staff member said she did not know where the lubricants were.

The use of lubricant helps reduce the risk of HIV transmission when men have sex with men.

She added they are offering PrEP, but most of the people who tested HIV-negative were not interested in taking PrEP.

She said only about one person a week was initiated on PrEP.

She added staff didn’t get any specialised training on how to deal with key populations, but said they were trained on government ethics and had written an online test.

At facilities monitored by Ritshidze, 92% of sites had external condoms available, only 75% had internal condoms available, and just 28% had lubricant available.

Lubricant availability, as measured by Ritshidze, improved dramatically from 2021 to 2022 and then declined slightly in 2023.

Need for continuous training

Lynn Bust, a project manager at the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation’s LGBTQI+ and health division, says data collection and sexual orientation workshops are important to better understand the needs of key populations.

She adds the foundation offers a four-hour sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) workshop that unpacks some of the strategies to get people to start thinking about what they can do as individuals and organisations to create inclusive environments.

“Staff need to be trained on SOGI concepts and providing LGBTQIA+ affirming care.

“This is important not just for healthcare providers but also for support staff such as security, receptionists, cleaners, and administration staff as they interact with LGBTQIA+ people and are often the first point of contact at clinics,” she says.

READ | Medical science has made great strides in fighting TB, but reducing poverty is imperative

Bust adds continuous training for people working with key populations is important.

“In our experience, one training session is not enough.

“Rather, an ongoing programme to learn about LGBTQIA+ people and their health needs is required.

“It takes time to change narratives, unpack stigma and dispel myths – so rather an ongoing discussion than once-off information overload.”

Bust says there is a need for explicit policies to protect not only patients but also LGBTQIA+ staff, including recruitment, leave, and adoption policies.

“Policies should clearly prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, and action to be taken against this should be clearly described,” she adds.

Bust says data collection is important to better understand the needs of key populations.

“We need national data in order to advocate for LGBTQIA+ health needs, and this is severely lacking in SA.

“If clinics were to collect and report on SOGI, we would know more about the number of patients and their health needs to better inform the services we provide for the communities.”

Government responds

Regarding government policies, national Department of Health spokesperson Foster Mohale refers to South Africa’s fifth National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2023-2028.

Without going into detail, he says it identifies possible interventions to be implemented to address biomedical, structural, and behavioural challenges faced by key populations in the country.

Mohale adds in 2023, the department adopted a health plan to affirm its commitment to increase access for key populations to quality and friendly services.

“The Key Populations Health Implementation Plan [KP-HIP]: 2023-2028 promotes the establishment of KP-friendly facilities and outlines the standardised packages of healthcare services to be delivered by sensitised healthcare providers to address the needs and interests of key populations,” he says.

The department, notes Mohale, runs continuous sensitisation training sessions to empower both clinical and non-clinical employees to respect the rights of key populations and provide healthcare services in an indiscriminatory manner.

“However, it is critical to mention that change in attitudes and behaviour are long-term goals. The tangible results may take longer to be evident and realised,” he says.

Mohale adds for purposes of enhancing accountability, facilities will continue to utilise the complaint boxes to regularly monitor the experience of key populations.

*This article was published by Spotlight – health journalism in the public interest. Sign up to the Spotlight newsletter.