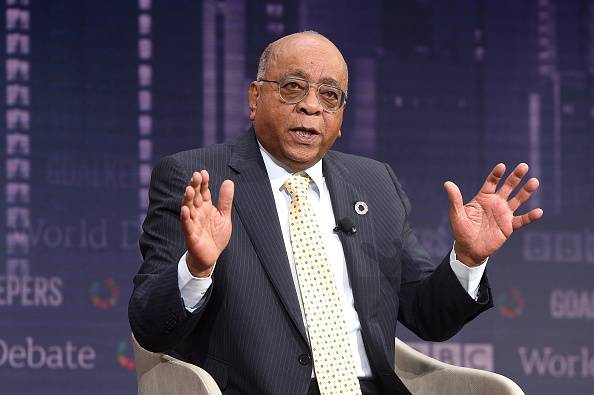

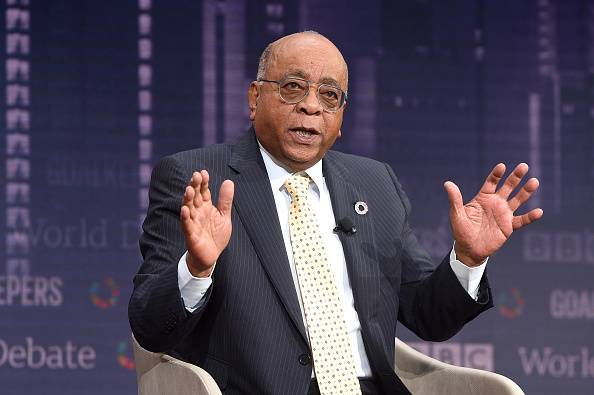

Ibrahim said there is hope for the continent's young people. (Mike Lawrence/Getty Images for Gates Archive)

Governance progress in Africa has stalled, with security and political rights deteriorating in many countries, according to the latest Mo Ibrahim Foundation report released on Wednesday.

“It's not pretty,” Ibrahim told AFP ahead of the report's release.

“Africa made great progress in the early decades of this century, but the past decade has shown that progress has been very slow…and in the past five years, the situation has begun to stagnate, and in some cases even worsen. ”

Ibrahim, 78, is a Sudanese-British billionaire who made his fortune in the telecommunications business and funneled it into monitoring and promoting better governance across Africa.

The foundation's index, published every two years, processes data on 322 variables, including public services, justice, corruption and security, and is considered the most comprehensive overview on the subject.

A new study found that 33 countries, home to just over half of Africa's 1.5 billion people, have made some progress in overall governance over the past decade.

However, for the remaining 21 countries, “the situation in 2023 will be even worse than in 2014,” with many showing signs of sharp decline.

Seychelles' rapid improvement has snatched the top spot from Mauritius, another Indian Ocean island nation, in the foundation's overall rankings.

Africa has seen several areas of low-level but widespread improvement, including infrastructure, women's equality, health, and education.

However, much of this is being undermined by declining scores on the rule of law, rights, political participation, and especially security.

“Lack of security affects everything. Who builds businesses and schools in conflict zones?” Ibrahim said.

'vicious circle'

Sudan, South Sudan and Ethiopia are among the countries that have experienced devastating conflicts in the past decade, and a spate of military coups in West and Central Africa since 2021 has underscored the fragility of political progress.

Ibrahim said pandemic lockdowns and a global trend toward “politics of the strong” may have emboldened dictators.

But his biggest concern is the “financial quagmire” in which African countries are stuck with high debt burdens and the high premiums they have to pay to get cash from global financial institutions.

“It's cyclical,” he said. “If you don't have enough money to build infrastructure or deal with health and education, you start to lose control and it affects security.

“We need to break this cycle to allow people to invest in their future.”

Ibrahim knows firsthand how difficult it is to invest in Africa. When he started an African telecommunications company in the late 1990s, banks refused to lend to him.

A separate report from the foundation found that the situation had hardly improved. Africa currently receives only 3.3% of the world's foreign direct investment.

Mr. Ibrahim points to the need for fundamental reform of global financial institutions and better skills training for Africa's vast youth.

The report is at the root of growing discontent among people on the continent. Even when indicators show positive signs, public perception is bleak.

The researchers said this may indicate that many of the most severely affected populations are not included in official statistics, and data gaps persist.

It may also reflect the phenomenon in which people's expectations and dissatisfaction increase as public services improve.

Despite all the gloom, Ibrahim sees hope in Africa's young generation.

“They are more informed, they are more entrepreneurial, and enough is enough,” he said.

© Agence France-Presse