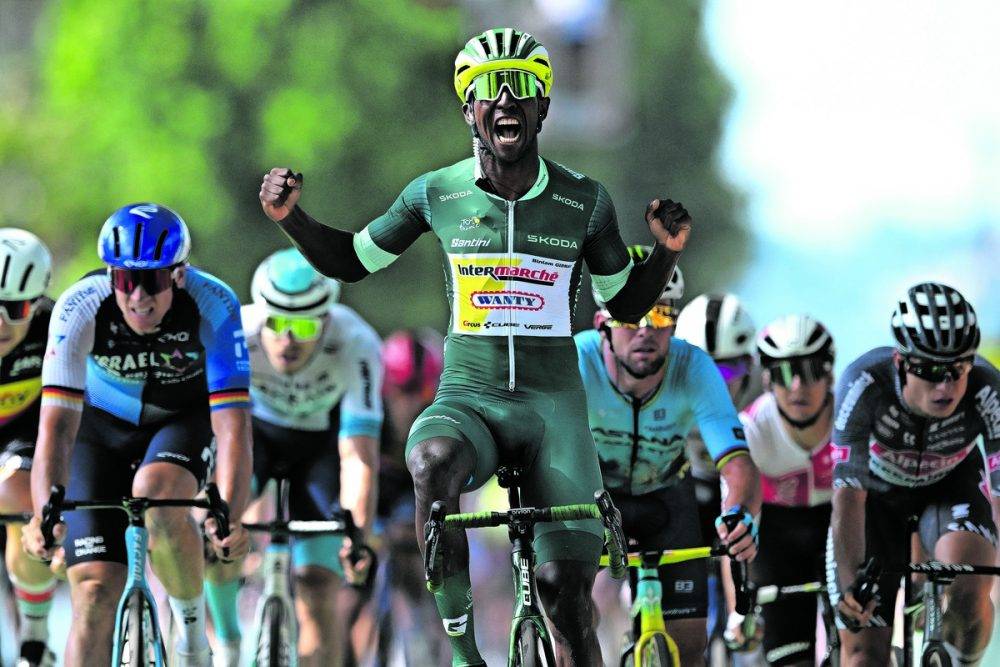

Eritrea's Biniyam Ghirmay celebrates at the finish line as stage winner of the 111th Tour de France 2024. (Jean Katouf/Getty Images)

a Just a split second before crossing the finish line in Turin, Biniam Ghirmay stood up on his bike.

He took his hands off the handlebars, smiled to himself, and punched the air in defiance as 175 of the world's best cyclists kept their heads down behind him and pedaled hard towards the finish line.

There was no bike in front of him.

The Tour de France is the world's oldest and most prestigious bicycle race, pitting cyclists against one another over 21 gruelling stages spanning 3,500km, through cities, up mountains and along winding, picturesque countryside.

It's one of the toughest races in world sport, and one of the most elite. In its 121-year history, an Eritrean had never won a stage. Never before had a black African won a stage. Until Ghirmay.

Not much was expected of the 24-year-old going into the race, but his win in Stage 3 was no fluke: He went on to win Stages 8 and 12 and now wears the iconic Maillot Vert, the green jersey usually awarded to the fastest sprinter (the polka dot jersey goes to the fastest climber, and the yellow jersey goes to the fastest overall cyclist).

“It was incredibly crazy, people were celebrating everywhere,” Ghirmay said.

The celebratory mood was particularly evident in the streets and bars of Asmara, the Eritrean capital, where cycling is a religion and Ghirmay is already a national hero.

“The plan was to get myself in shape for the Olympics and I feel pretty much in top form right now,” Ghirmay said. “My first goal is to finish the tour safely.”

Perhaps he was testing fate.

Just a few days later, in the final few hundred metres of Stage 16, on a flat course perfect for his specialty sprint finish, Guillemay crashed while going through a roundabout at high speed.

His teammates helped him to his feet and he pedaled carefully to the line, but he had lost the stage to his closest rival, Belgian rider Jasper “Disaster” Philipsen, and retention of the green jersey suddenly felt more precarious.

Undaunted, Ghirmay pulled himself together, got a good night's rest and then beat Philipsen in a mid-mountain sprint the next day to re-stretch his lead – a few bruises and scrapes were hardly going to slow him down given the obstacles he'd overcome to get to this point.

Bicycles were first brought to Eritrea by the then-occupying Italian army in the late 1800s, and cycling quickly became popular. Initially, bicycle racing was strictly segregated, and Eritreans were not allowed to compete against their colonial masters.

In 1939, Italian authorities organized a special race between Italian and Eritrean athletes, ostensibly to prove Italian superiority, but it backfired and the race was won by Gebremariam Gebru, whose victory is still celebrated today because, in the words of the Eritrean Ministry of Information, “this victory shattered the Italian colonial myth of Eritrean inferiority.”

Since then, Eritrean cyclists have continued to prove their mettle in the face of enormous obstacles: at home, they have had to contend with civil war, diplomatic isolation and one of the most authoritarian governments in the world.

As African Arguments reports, this situation could also be a counterproductive incentive, since professional cycling is one of the few ways for athletes to avoid mandatory indefinite national military service, as long as they are fast enough.

But the country's high altitude and relatively quiet roads, a result of its stagnant economy, provide ideal training conditions. Those who make it must enter the cutthroat, expensive and sometimes racist world of international cycling, where opportunities for African riders are few and far between.

Girmay hopes his success will change that: after his first stage win, he posted a photo to social media with the caption “Let me open the door.”

“This is a huge opportunity for African cycling and especially for my country,” he said, urging international cycling's top teams to invest more in the continent's talent.

“My team has invested so much into me that I need them to invest in me, and now it's time to pay them back.”

“Other teams are doing the same thing. [African cyclists] Also.”

It's a common refrain in Africa's growing cycling community.

Despite the huge potential of young talent, cycling clubs in Africa have survived largely thanks to the self-sacrifice and collective support of members driven by goodwill and passion for cycling.

They often survive despite leadership problems and national cycling federations struggling to raise funds.

Cameroon's most famous cyclist, Kamzon Abesero Clovis, is one of the few Africans who can make a living from the sport.

He considers himself lucky to be on a team that pays him a salary and training bonuses, and he said African athletes need more opportunities to compete.

“Competition is the lifeblood of an athlete,” he says. “Training doesn't help you progress the way competition does.”

Girmay's dominance in this year's Tour de France is evidence of what can happen when African cyclists get the support they need. He showed exceptional early promise, earning him a rare spot at the World Cycling College, the international cycling body based in Switzerland, which caught the attention of his current Inter Marché Wanty team.

He then started riding his bike and got noticed all over the world, and he's still riding it today.

This article was first This article was first Continenta weekly newspaper distributed across Africa. Mail & GuardianDesigned to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Download the free version. here