IIn 1976, the Tate announced in its bi-annual report that it had purchased Carl Andre's equivalent VIII, a 1966 sculpture composed of 120 regular refractory bricks. The light-colored bricks are placed directly on the gallery floor, with six bricks horizontally and ten vertically stacked in two layers in a neat rectangle. The Tate still exhibits them from time to time as classic examples of minimalist art. Even if the viewer looks down to avoid its succinct, unyielding, low-slung presence, there's not much to make them pause. It's a statement, if not a particularly deep one.

It's not particularly confrontational or enveloping, and the materials and their arrangement are familiar, so it's unlikely to provoke a shrug, much less a debate. If there was once a mystery as to why they were there, that is long gone. This is what certain artists were doing back then, and they still do similar things today. We are used to all kinds of provocations in the gallery. But for a long time, Andre's bricks (which became known as Tate bricks) caused great controversy, generating newspaper headlines, heated debates, and numerous caricatures and tongue-in-cheek photo opportunities. Ta. The bricklayers offered to make a cut-price version, and the Daily Mirror reported under the headline: “Work of Art: Brickbats made by boys on a building site”: A smiling bricklayer holds his own version of Andre's sculpture. I posted a photo of. Oh, how I laughed.

Andre's eight comparable sculptures all used the same number of similar bricks arranged in different configurations, but not as much as the herringbone pattern and decorative squares of London architectural bricks depicted in The Mirror. There was nothing fancy. Andre's sculpture was also the basis for an attack by the Conservative opposition on Labour's cultural policy. André's Equivalent Sculpture takes its title from Alfred Stieglitz's famous series of photographs of clouds, and like many of his works, he was a brakeman on the Pennsylvania Railroad, working on connecting and shunting chains. I was also inspired by his four years of work. A freight car from the early 1960s. This work not only provided him with an income, he said, but also took him away from the pretense of art. His grandfather and uncle were bricklayers and building contractors, but this fact was never reported in the British press.

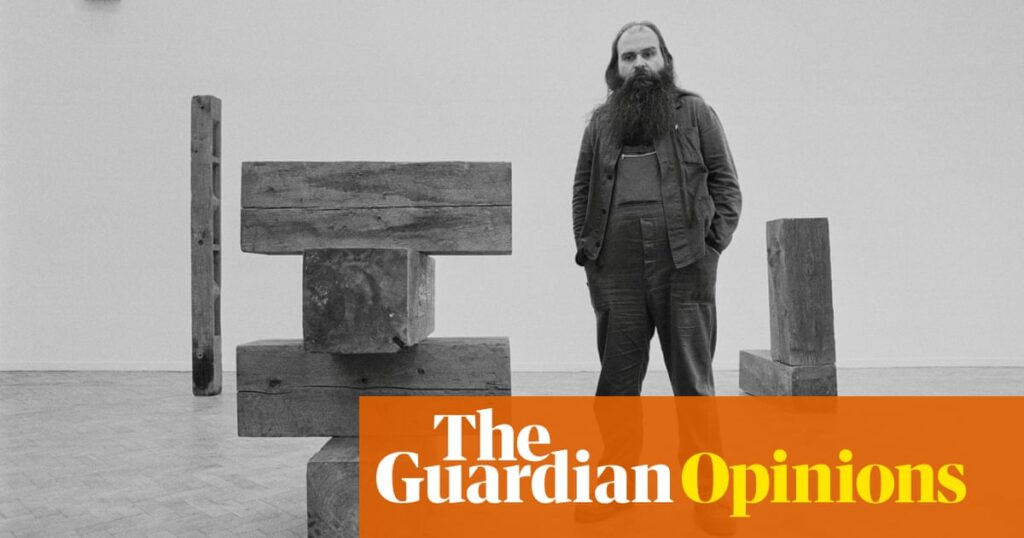

Andre made sculptures and wrote poems, as well as rearranging carts of steel, wood, and coal. He stacked and arranged objects, arranging them in regular rows, squares, and rectangles. Sometimes they were crooked. All of this recalls both his work in the freight yard and the broader context of Massachusetts' urban and industrial setting. When the boy from Quincy, Massachusetts, was a teenager, he visited his aunt in England and went to see Stonehenge. This, and subsequent visits to Kyoto's gardens, had a lasting impact.

That was all a long time ago, and with Andre's death in hospice at the age of 88, the ideas and idealism of minimal art are now thoroughly absorbed, digested, analyzed and critiqued by another It feels like the passion of the times. Whether you recognize them as art or not, you could easily trip over Andre's low stacks as you walk across the gallery to see something else. Viewers in the 1960s weren't used to having to look down at art so close to the floor. Soon, Andre began creating interspersed pieces of tiles, lines and grids of zinc, aluminum, and sheet steel, which viewers were invited to actually walk on. They were rather beautiful, even though they were scuffed and scratched by people's footwear. It was more than just a display of materials in all their variety and difference: muted metallic grays with variations in reflectance, warmth, weight and mass: it was a space, an idea of sculpture as a place. The core of what he did. Andre's career continued rapidly for a long time, with exhibitions in museums, famous galleries, and acres of erudite expositions. Like Richard Serra, he and Minimalism were canonized, even though he rejected the word.

Somehow, like his audience, young artists had to find a way to negotiate with Andre without stumbling or stumbling. He brought up Taoism and the simple idea of being there and slowing down. No matter how radical it once was, no matter what his sculptural achievements were, no matter how seductive and understated it was, André's work has seen diminishing returns over the past half-century. I've been doing it. Artistic consistency and rigor can sometimes feel repetitive, the same old. But no one went to Andre for novelty. It's always the same and always different, like looking at the ocean.

If you run into Andre when you turn the corner at the gallery, you might be in for a nice surprise. But despite all the little controversies it caused, I didn't think about the death of my young man as I looked down at Andre's bricks, stepped on the metal sheet floors, and gazed at the architecture made of hewn ash and cedar wood. It has become almost impossible to do so. Andre's third wife, Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta, died one night in September 1985 after falling from Andre's 34th-floor apartment in lower Manhattan.

They had been drinking and were alone. Neighbors heard them arguing. Mendieta was 36 years old and she had been married for eight months. Two days later, Andre was charged in connection with her death. He was never found guilty. After Mendieta's death, Andre's career took a downturn. He was nicknamed the “OJ of the art world” after O. J. Simpson, and his shows were picketed. At one opening ceremony in New York, more than 500 protesters showed up holding signs that read “Where's Ana Mendieta?”

Although some friends defended him (particularly Frank Stella, who helped pay for his bail and defense), others cut him off. Andre continued to live in the same apartment and remarried, but his personal and artistic reputation never fully recovered. In his later years he developed dementia. Although large-scale museum exhibitions continued in Europe after Mendieta's death, they ceased to be held in North America for almost a quarter of a century. For a long time, catalog essays avoided mentioning Mendieta's death, even a serious one.

Andre's art had limits and limits. He did his own thing in every sense of the word and did not have much contact with the academics and theorists who played a big role in the development of his artistry. He remains a divisive figure. In 2022, American curator and author Helen Molesworth produced a lengthy podcast series examining Mendieta's death. This is the best explanation I've come across of what happened that night and its impact at the time, in light of the #MeToo movement and today's cultural politics.

A dissection of art world conventions, money and morality, and righteous indignation, Molesworth's Death of the Artist is more than a skewering of one man's reputation, it grapples with the difficulty of viewing his art today. I'm here. Can you still enjoy the work of an artist you personally disparage? Molesworth is by no means to be taken lightly, and this utterly fascinating exploration of personal politics and the politics of the art world remains It brilliantly deals with the ambiguity and ambiguity of Andre's life and art, which are inseparable.