A version of this article was originally published on 19 February, 2019.

The power of sport means certain matches can seem like seminal cultural events. For Wales, their win over England in 1999 was an era-defining moment.

There was blazing sunshine, Tom Jones singing on the pitch and the incongruous sight of Wembley Stadium filled with swathes of red Welsh shirts.

Even 25 years on, 11 April 1999 is still etched in the national consciousness.

Wales were playing their home matches at Wembley while the Millennium Stadium was being built. While Welsh rugby at the home of English football was an uneasy fit, this would prove to be a landmark victory.

With the benefit of hindsight, 1999 was a year that produced green shoots of recovery for Wales, without a Grand Slam since 1978 but in the early throes of a 10-match winning run.

This team were tasked with dragging Welsh rugby off the canvas at the end of a dire decade and, although they did that, they would admit they were not among the best in the country’s history.

Unlike their trophy-laden predecessors, this vintage had enjoyed precious little success and started this Five Nations campaign in underwhelming fashion, losing to Scotland and Ireland.

They responded with a spectacular 34-33 victory over France – their first in Paris for 24 years – but most expected normal service to resume on the final weekend against England.

Wales had lost each of their previous five matches against their arch-rivals, who were in fine form and one win away from a Grand Slam.

“It was our last game at Wembley. It was a special place, knowing England were going for the championship,” says Scott Quinnell, Wales’ number eight that day.

“They were a brilliant side with great people, growing towards that [2003] World Cup-winning side.”

To even say Wales’ supporters travelled to Wembley that day in hope rather than expectation would have been a stretch. Welsh optimism in this fixture was in short supply.

But regardless of their dismal recent record against England, the red-shirted masses descended on Wembley by the busload, turning an English institution into a cauldron of Welsh noise.

If the concept of Wales playing at home against England in London still seemed strange, then Wembley’s temporary tenants did everything in their power to ensure this was as close to a Cardiff matchday experience as one could hope for.

Just six years older than the mascot that day, England’s 19-year-old wing Steve Hanley was making his international debut.

“I reckon I’ve got more recollections of the day than anyone else because it was my first cap,” he says. “I can remember everything from the moment I woke up to when I went to bed.

“It threw you when you got there and there were 76,000 Welsh there. It was quite surreal, getting on the bus with a police escort to the ground.

“Tom Jones was playing Delilah when we walked out and that’s when we realised we weren’t in England, we were in Wales for 80 minutes.”

Bathed in glorious springtime sunshine, Jones was among a raft of pre-match performers, including Welsh folk hero Max Boyce, who had updated his 1970s favourite ‘Hymns and Arias’ for the occasion.

“It was like a carnival atmosphere,” says Boyce.

“I’ll always remember I was singing and the England players were on the field practising and the ball bounced towards me – and Matt Dawson, the English scrum-half, came right up to me and said: ‘My mother loves you!’ I’d never met him before!”

Without his guitar and with the company of 76,000 in the crowd, Boyce says he was “daunted” by the prospect – but he showed no signs of nerves in a set brimming with his usual showmanship.

Boyce then joined forces with Jones and a male voice choir for a particularly powerful rendition of the Welsh national anthem.

“It was incredible,” says Quinnell.

“To take them on with all the emotion, Tom Jones was there before the match, and Max Boyce was there. [Then Wales coach] Graham Henry said, ‘Come on, you’re not concentrating’, and got us back in the changing room. He read us the riot act.

“I think we were getting carried away with it. We’d won in France for the first time in 24 years and we’d come back with a spring in our step.

“If there were only 76,000 people there, I know more than 500,000 people who’ve told me they were that day!”

The match

Emotions were running high and hope swelled among the Wales fans. With such a fervent atmosphere, surely there could be no stopping their team.

Unfortunately for them, England were not obliging guests and raced into the lead through Dan Luger’s try within two minutes of kick-off.

England seized the initiative with a 19-year-old Jonny Wilkinson at outside centre and his fellow teenager Hanley crossing for their second try.

“I never felt so in control of a game. We scored three tries to none but we were only leading by seven points at half-time,” Hanley says.

“Psychologically, we felt massively in front but Wales were still within one score.”

That was thanks to Wales’ fly-half Neil Jenkins, whose six penalties had limited a seemingly rampant England’s lead to 25-18.

His punishing accuracy was just about Wales’ only weapon in the first half but, gradually, they were clawing their way back into the contest.

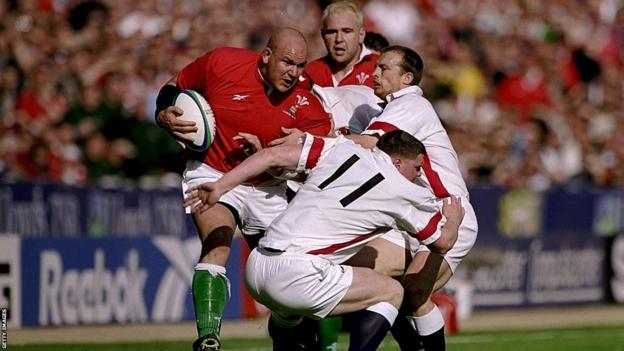

The first swing of momentum in Wales’ direction came as they trailed 15-9 in the first half, with a bludgeoning carry from Scott Quinnell’s younger but even bigger brother, Craig.

The second row found himself in unfamiliar territory on the right wing, cantering towards Dawson – who he swatted aside with ease – before honing in on Hanley, who he sent sprawling backwards, the debutant a mess of arms and legs on the floor.

“When Craig ran down the right-hand side and ran over Steve Hanley, that gave us that spirit,” says his brother Scott, who had the best view in the house as he ran in support close behind.

Just a few minutes earlier, Hanley must have thought international rugby was a breeze after marking his first appearance with a try.

“I remember the first half, I remember scoring a try and I remember getting bulldozed by Craig,” he says, able to laugh at the incident by now.

Even after Quinnell’s rousing run, Wales managed to concede a third try in calamitous fashion, with Gareth Thomas and Shane Howarth colliding as they both tried to collect a high ball, lying dazed on the ground as Richard Hill touched down for a try that Wilkinson converted for a 25-15 England lead.

Thanks to Jenkins’ metronomic goal-kicking, that score was not as damaging as it might have been – and the Wales fly-half demonstrated his handling skills with a fine miss-pass to Howarth, whose converted try brought his side level at 25-25 in the second half.

Wilkinson restored England’s lead to 31-25 and, with just a few minutes left, they were awarded a penalty in kickable range.

Another three points would have left Wales needing at least two scores but, looking to seal the Grand Slam with a flourish, captain Lawrence Dallaglio told Wilkinson to kick to touch as England aimed to finish the match with a try.

“When England turned down the kick at goal – and that wasn’t something that happened every day – we said to each other: ‘Come on guys, if this is what they think of us, then we’ve got to turn it around’,” Quinnell says.

“Then Colin Charvis won a penalty and Neil Jenkins with an incredible kick got it into the English 22, and then ‘The Try’.”

‘The Try’

With rugby union then still employing added time rather than stopping the clock for breaks in play, there were more than 81 minutes played when Jenkins’ towering kick put Wales in a prime attacking position.

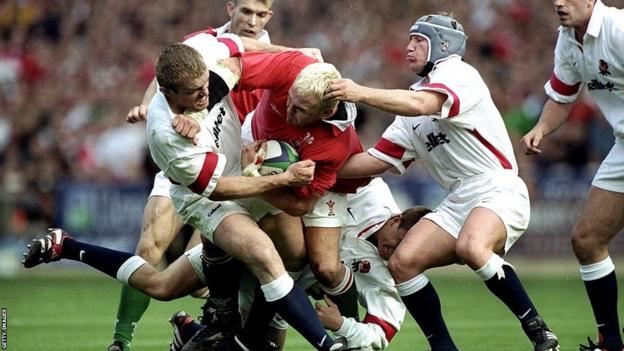

They called a shortened line-out and hooker Garin Jenkins threw to the middle, where Chris Wyatt gathered and popped the ball down to scrum-half Rob Howley.

Howley passed to his left but, rather than fly-half Jenkins, the man standing at first receiver was the imposing number eight Quinnell.

Expecting him to come bulldozing straight towards them, England’s defenders closed in on the bleach-blonde Llanelli back-rower in anticipation of an explosive collision.

“I remember Gibbsy [Scott Gibbs] said, ‘Just give me the ball!’ We talked about this move before but we’d never practised it because it involved me passing the ball so there was no point,” Quinnell recalls, beaming at the memory.

“I thought I’d bobble it just to bring the defensive line up! If you believe that, you’ll believe anything.”

With Charvis on his shoulder as a decoy runner, Quinnell almost spilled the ball before gathering it and passing to Gibbs, who had come crashing into view, hurtling at full pace, having made his move from a deep, angled starting position.

In what felt like a blink of an eye, the white wall of English defence had disappeared, Gibbs cutting through a slither of a gap untouched and now in space inside the opposition 22.

“I managed to get the ball to Gibbsy, stood back and thought he was just going to run over Matt Perry,” Quinnell adds.

England were not in panic mode yet. Gibbs was renowned for brute force rather than fancy footwork – an inside centre arguably most famous for a monumental dump tackle on South Africa prop Os du Randt during the British and Irish Lions’ 1997 series win.

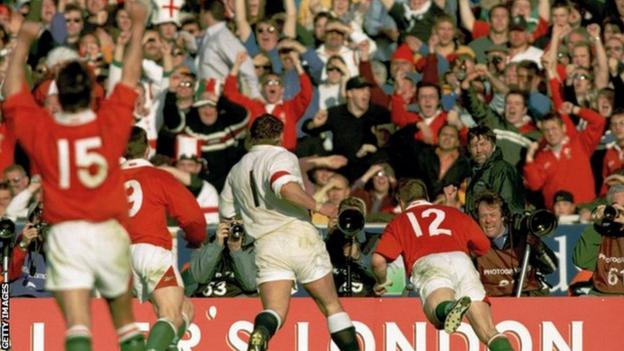

But on this occasion Gibbs was devastatingly light on his feet, evading Dawson’s ankle tap, skipping past Perry’s despairing lunge and then, with a bounce as if the Wembley turf was a trampoline, sidestepping around Hanley and crossing the line with his arm aloft in celebration.

“I remember racing across and I didn’t have any chance of stopping Scott,” says Hanley.

“Most people watching on the day would have been expecting him to put his head down and barge through but that try summed him up really.”

It was a virtuoso score, and from a move which Wales had never attempted before.

“We’d done it in training a few times but it was one, luckily enough, we kept back for a special occasion,” says Quinnell.

“If you’re only going to use that move once in your life, that was the day to do it.”

Gibbs was confident he could change the game.

“I remember telling Lawrence Dallaglio at the back of the line-out, ‘I feel good tonight’,” Gibbs told S4C.

“I knew something special was going to happen. The fact Scott juggled the ball caught their eye. It was so good. It was balletic!”

Wales’ players and fans were in raptures but, behind Gibbs, there was one voice imploring caution, that of fly-half Jenkins, who still needed to convert the try to give Wales victory.

“Gibbsy is a good friend of mine and he was putting his arm up and waving, and I was more concerned about him going underneath the posts because I knew we were losing,” said Jenkins.

Even for a kicker as prodigiously accurate as Jenkins, this conversion was no formality, despite Gibbs’ judgement.

“Jinx [Jenkins] said, ‘Gibbsy why couldn’t just have put it under the post?’,” said Gibbs.

“So I threw him the ball and just said, ‘kick the thing’. I didn’t even watch the kick. I knew 100% he would kick it. No problem.”

Slightly to the right of the posts, it was the kind of kick you would expect Jenkins to stroke over blindfolded in training – but these were exceptional circumstances.

With the game deep into added time, the boisterous Wembley crowd fell silent and, for the eighth time that afternoon, up stepped Jenkins.

“Sometimes as a kicker you have those days and, luckily for me, I had one of those days,” he says.

“I managed to nail all the kicks prior to it and there had been a few during the game, so I was feeling confident.

“It was an incredible try and it deserved the kick to go over and luckily it did.”

Ever the man to deflect praise, even many years on, Jenkins is not entirely comfortable reliving his moment of glory.

His coach that day, Henry, was more obliging.

“I have never seen a kicking display better than that,” the New Zealander said after the match.

“If the posts had been two metres apart instead of 10, Neil Jenkins would still have kicked all his points.”

The aftermath

Jenkins’ kick was not quite the final act. Wales still had a couple of minutes to survive.

England came at them again and got into drop-goal range. Trailing by a point, one kick would be enough for victory and the Grand Slam.

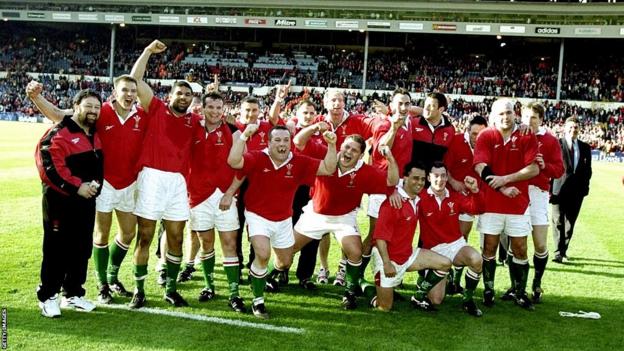

But Mike Catt’s mishit effort fell into the arms of Howarth, who caught the ball and gathered himself before booting it into touch to prompt the final whistle and, with it, scenes of pandemonium in the stands.

Wales’ players were equally delirious, embracing each other on the pitch and basking in the rare glory of a win over England, their first since 1993.

England, by contrast, were crestfallen. Their hopes of a Grand Slam had been shattered and they did not even have the consolation of a title, which Scotland won.

“I remember Clive [Woodward, England’s head coach] walking around the changing room and, individually, told everyone in there that lessons learned that day would help us win a World Cup,” says Hanley.

“We were devastated, not only because we’d lost to Wales in our own country but we’d lost a Grand Slam.

“There’s a lot of the Welsh lads I’m still in touch with, like Scott [Quinnell]. I still get s**t off them all the time!”

The nucleus of that side went on to help England win the 2003 World Cup – but the triumphant team in Australia did not include Hanley.

The agonising defeat at Wembley would prove to be the wing’s only cap for England.

While Hanley and his team-mates wallowed, the celebrations were in full swing for Wales and Scotland, who were crowned the final Five Nations champions before the competition became the Six Nations in 2000.

“Everyone in Wales was crying,” said Gibbs.

“I think it was the perfect day, 32-31.”

It was an unforgettable day for Wales’ players but, such was the nature of their post-match revelry, their recollections of the evening are a little hazy.

“I can’t remember,” says Quinnell with another laugh.

“My mate John came round, we’d had a few beers, he fell asleep and I think he woke up with his car keys, his watch and his phone all in a pint.

“I worked a lot with [former England centre] Will Greenwood and he’s scored hat-tricks against us, scored tries for fun against us, but I can always say: ‘Remember when we stopped you winning the Championship in 1999 and Scotland won it because they beat France?’

“When we got back to the hotel on Monday morning, the Scotland team had sent us a bottle of whiskey each to say thank you for doing it. That was a lovely touch.”