Diane Lynn was left pitchside in a state of disbelief when a rival fan offered her tea.

On a sunny spring afternoon in 1989, the bodies of Lynn, then 22, and her 17-year-old brother were pulled from the crush at the Leppings Lane end of Sheffield's Hillsborough Stadium.

The clash ultimately resulted in the deaths of 97 fellow Liverpool fans.

Lin and her brother were in one of the two central cages where the tragedy occurred.

“I knew I was going to die,” Lin says.

But she survived, and in a blur she clambered up to another part of the Leppings Lane terrace and found herself standing on the adjacent pitch in front of the South Stand.

There she prostrated herself in front of a group of Nottingham Forest supporters. Her fans were the same Liverpool fans who traveled to South Yorkshire to watch their team in the FA Cup semi-final.

“We collapsed near Nottingham Forest fans and they offered us tea and coffee from flasks,” Lynn told the BBC Sounds podcast. Unprecedented Hillsborough: Nottingham Forest fans.

“I want to know who they were. They helped us. They calmed us down. My brother, I've never seen anyone so shocked. He He was so pale that he couldn't talk, and I still can't.'' We never talked about it, so I don't know what he saw.

“One of the fans at The Forest was a father of several children. You wonder now what those poor young children saw.”

No one was killed among the 28,000 Forest fans in attendance that day, but Britain's worst stadium disaster unfolded before their eyes.

And for much of the 35 years since, they have remained Hillsborough's silent witnesses.

Now, as vice president of the Hillsborough Survivors Support Alliance (HSA), Lynn has helped some Forest fans come forward with what happened and come to terms with the horrors of Hillsborough.

“The people of Liverpool need to listen to Nottingham Forest fans,” she said.

“They need to know exactly what happened to them, what they saw, and that they were part of that tragedy.”

That's why she responded to Forrest's tweet in 2021, marking the 32nd anniversary of the earthquake, with a message of support for the fans who were there.

she signed a contract HSA response By writing, “We are here for everyone.”

Those five words meant a lot to Forest fan Martin Pietsch.

“That was a great moment,” he says.

“I remember thinking, 'Wow, this is the first time I've seen a realization that Forest fans might have been influenced by what they saw that day.'

“It was such a relief to be recognized and the response from Forest fans to it was so overwhelming.”

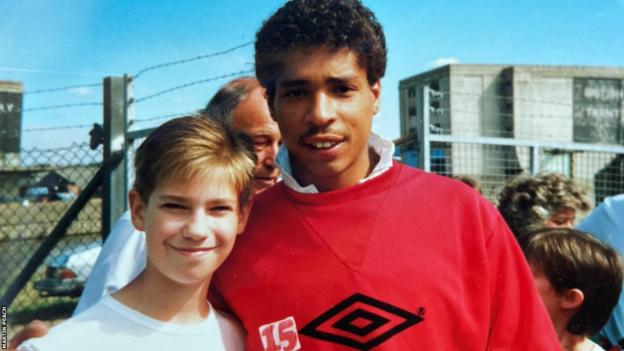

In 1989, Peach was 12 years old and sitting in the south stand near Hillsborough's fenced Spionkop end. Thousands of fellow Forest supporters stood on the terrace behind the goal, facing the unfolding disaster.

“I remember that day more clearly than any other day in my life. I've thought about it every day for 35 years,” said Peach, who now has a 12-year-old daughter.

Police set up a cordon around the halfway line, and a Liverpool fan with long hair, a beard, ripped jeans and a leather jacket, dressed as an '80s rocker, broke through the line and faced the Forest fans in despair. This includes the image of him running. A scene burned into his mind.

“He ran as fast as he could down the pitch and got to the goalmouth in front of the Kop in front of 20,000 Forest fans. And he just dropped to his knees and screamed at the sky,” Pietsch recalled.

“That was the first moment Forest fans thought: 'Something is wrong. This is not a pitch invasion. There is something seriously wrong.'

“It was a massive event that had a huge impact on me as a young child, and it remains a scar on my brain because I had no way of talking about it or sharing it.

“The game was on Saturday, and I went back to school on Monday to continue playing. I think my parents asked me if I was okay, but I don't remember discussing it in detail.”

Peach was a music-loving and football-obsessed child from Swanwick, a small village on the Derbyshire side of the Nottinghamshire border.

He was not the only young man from the old mining community to attend the match. Two 18-year-old Liverpool fans from the local area also made the trip.

“One of them went home, but the other didn't,” Peach said.

“That’s why Hillsborough was so important to me.

“If I had chosen to support Liverpool instead of Forest, or if we had been on opposite sides that day, how easy it would have been for me not to have gone home that day.”

For over an hour, Peach was among the fans in the forest who could only watch.

At least one Forest fan sitting beside him attempted to enter the pitch to assist with first aid, but police prevented them from entering.

A 2016 autopsy revealed there were 96 fans. I turned 97 years old – was unlawfully killed Police mistakes are occurring frequently.

It took 27 years for that verdict to be handed down.

Survivors and their families campaigned for 30 years to find out what caused the deaths.

Forest fans on the other side of the pitch that day, just 100 yards away, were struggling to understand the gravity of the situation.

Peter Hillier, then a 25-year-old Forest fan, would take the train from London and join his father and brother at the Kop in Hillsborough to cheer on the team as they challenged for major national and international honours.

Forest have been battling Liverpool for some of the game's biggest prizes for more than a decade.

Conflicts were intense and tensions between supporters were often high. Crowd troubles were common.

Mr Hillier said that when he first saw people trying to climb over the fence on the terraces of Leppings Lane, his “initial suspicion” and that of many at Forest End was that it was a pitch invasion. admitted that it was an attempt.

“That's what happened back then,” he says.

“Then people hurled abuse. Once you saw people in despair, things changed.

“Then the gates were opened and people started to be carried out and Liverpool supporters were tearing apart the advertising warehouse to remove people who were believed to be injured.”

A large number of people were carried away on makeshift stretchers and laid out in front of the forest supporters in the penalty area.

“We saw that these people didn't have broken legs. We saw people trying to resuscitate people and save people. And then we saw them stop,” Hillier said. says.

“Somewhere along the line, I realized someone had died there.

“I was numb because I couldn't do anything. By then it was silent. There was no more chanting or cursing. I was confused.”

Hillier let his father and brother talk on the terrace, but they said nothing about what they saw or the years that followed.

“We stood there because we didn't want to be there,” he says.

“Seeing 97 people killed is not a normal human experience.”

In the years that followed, Hillier said she had recurring nightmares, struggled to form relationships and struggled with alcohol problems.

He feels he, like the majority of Forest fans, reacted by bottling up the trauma.

“There was a sense that it wasn't going to happen to us,” he says. “We were there too, but this is a tragedy for Liverpool and we are a byproduct of that.”

The perception of forest enthusiasts on Merseyside was tarnished by what then forest manager Brian Clough said about the disaster.

Clough, who led Forest to an English title and two European Cup wins, repeated his infamously inaccurate claim that Liverpool fans were to blame for what happened.

Clough later apologized for his comments before his death in 2004.

“It caused a lot of resentment and probably an assumption in Liverpool that everyone in Nottingham felt that way,” Hillier says.

“He was a hero, and he still is my hero, and he made a mistake in that. If people dig deeper into it, they'll see that he gave the wrong advice.

“He retracted it much later, but the people of Liverpool will say it was too little, too late.”

Hillier and Peach were among the Forest supporters who created a giant banner calling for an end to the tragedy chants and for respect to the 97 fans who lost their lives in the Hillsborough tragedy. It will be unveiled for the first time at Anfield in 2023.

Amanda Stanger, a Forest fan who was in the South Stand at Hillsborough in 1989, said the memory of that day “will never fade”.

She now works in a prison and has started having flashbacks when she sees people on the other side of the fence. She has had panic attacks in crowds.

But her biggest worry is what her fellow supporters will chant every time Forest play Liverpool. Forrest plays for Liverpool after her club ended a 23-year absence from the Premier League, and she has only become a regular again in the last two seasons.

“My anxiety levels are through the roof,” she says.

“What should I do, what should I say, I can’t ignore it.

“We experienced it only recently, but Liverpool supporters experience it every game, regardless of who they play.”

Mr Stanger was once invited by the anti-discrimination charity Kick It Out to meet a Forest fan who was found to have been chanting tragedy.

“The shock was that his father was in Hillsboro,” Stanger said.

“I asked him, 'Why did you do that, what about your dad?' He thought it was okay because his dad didn't talk about Hillsborough, but it told me a lot. It's telling that he doesn't talk about it because he's probably emotionally incapable of talking about it, not because he doesn't want to talk about it.''

In recent years, Stanger has found solace in talking about her experiences.

She accepted an offer for HSA-funded treatment and has since set up the Nottingham branch of the alliance.

She says she was “terrified” when she first arrived at Anfield to attend an HSA meeting. After that, it was as if she had “found a new family.”

“When I sat there and was asked to introduce myself, I got emotional,” she says.

“I said, ‘I’m Amanda, I’m a Forest supporter and I was at Hillsborough.’ Then someone turned to me and said, ‘You’re a survivor, you’re one of us. “said.”

“Nobody ever said that. You don't consider yourself a survivor. You consider yourself a supporter of the forest that was there. Nothing more. There is nothing.”

Every time she comes to her home base in Liverpool, she visits the Eternal Flame Memorial and remembers all those who lost their lives.

Standing in front of the memorial service, she tearfully explained what it meant to do something at Forest's City Ground to remember the tragedy that brought together the Reds on the banks of the Trent and the Reds on Merseyside. I explained while playing.

“This is what Forrest needs. A place where he can go and cry and say I'm sorry, I'm sorry, it shouldn't have happened,” Stanger said.