Kangpokpi/Imphal, India – On Christmas Eve, it was eerily calm inside a makeshift bunker with piles of gunny bags and a tin roof. Hunkered inside and clutching their single-barrelled rifles, 19-year-old Chonminlal Kipgen and 26-year-old Paolal Kipgen from the predominantly Christian Kuki-Zo community looked out and scoured the hills of Kangpokpi district for armed fighters from the rival Meitei community.

They said they were village volunteers – civilians who had taken up arms to defend their homes.

Not so far away in Manipur’s capital, Imphal, the majority-Meitei community had similarly muted celebrations during their most cherished festival, Ningol Chakouba, in early November.

For the past 11 months, the two communities in India’s northeastern state of Manipur have been locked in what is arguably the country’s longest-running ethnic conflict in the 21st century under the watch of a federal government headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The conflict has killed 219 people, injured 1,100 and displaced 60,000. It has revived an array of armed groups, sweeping up men and boys as recruits from both communities. On Saturday, two Kuki-Zo “village volunteers” were killed and their bodies allegedly mutilated in Manipur’s Kangpokpi district. In their press release, tribal groups accused “central security forces, who aided Meitei militants” of being behind the killings.

The conflict is frequently oversimplified as a struggle between the Hindu Meitei and Christian Kuki-Zo communities, mirroring the religious polarisation seen in communal conflicts and assaults on religious minorities in various parts of India. While the Kuki-Zo communities are almost entirely Christian, the Meitei community predominantly follows a syncretic form of Hinduism and their own Indigenous faith system, called Sanamahism. A smaller number of Meitei people also follow Christianity and Islam.

But an assessment prepared by Assam Rifles officials in Manipur highlighted a different set of factors that are unique to the conflict in Manipur. The Assam Rifles is the federal government’s paramilitary force with a long and controversial history in the state. It is the oldest paramilitary force in the country and shoulders the responsibility of maintaining law and order in the northeast along with the army.

The Reporters’ Collective (TRC) reviewed the assessment, made in a PowerPoint presentation, late in 2023. The officers who showed the presentation wished to remain anonymous. They took me through the presentation, which was in sync with the views one of the officers shared with me while explaining the reasons behind the Manipur conflict.

The presentation put part of the blame on the state government, headed by Chief Minister N Biren Singh, a member of Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and his “political authoritarianism and ambition”.

It is the first candid assessment from a federal government agency that has made it into the public domain.

It is significant because Modi this month, in the run-up to a general election, had asserted that the federal government’s timely intervention had led to a “marked improvement in the situation” in Manipur. This was one of the few times that the prime minister had spoken of the conflict. Meanwhile, the federal home affairs minister has placed his faith in the chief minister’s ability to bring peace, which so far has not provided a resolution. The state’s two seats in India’s lower house of parliament vote on April 19 and April 26, in the first two phases of the national elections.

The assessment by the Assam Rifles listed causes of the conflict as determined by officers in the thick of the violence.

It highlighted the impact of “illegal immigrants” from neighbouring Myanmar, the consequent demand for a national register of citizens to reduce migration and the demand for Kukiland.

Kukiland is a separate administrative unit that the political and armed Kuki leadership wants cleaved out of Manipur. The demand for Kukiland has been revived during the ethnic conflict.

Additionally, the presentation asserted that armed groups from the Meitei community are equipping people with weapons, and the Kuki community’s armed groups are backing “volunteers”.

All of this has intensified tensions and contradicted attempts by both communities’ leaders to present the conflict as common citizens volunteering for self-defence against the other community.

TRC could not independently verify if the views in the presentation are endorsed by the Assam Rifles as an organisation. Detailed questions were sent to the paramilitary force’s official spokesperson.

Initially, a spokesperson said the Assam Rifles would not be able to respond to something that was “hearsay”.

In a follow-up email, the Assam Rifles said it would “respectfully decline to engage in discussions regarding speculative or unverified matters. As a professional institution, we focus on our core duties and responsibilities, and we have no further comments on this issue at this time.” Later, it asked for a copy of the presentation.

The Assam Rifles did not respond to TRC’s follow-up emails asking if it held the views reflected in the presentation.

Queries to the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Manipur chief minister’s office remain unanswered.

The chief minister’s role

The immediate trigger for the violence was a demand by the dominant Meitei community for Scheduled Tribe status, a form of affirmative action granting quotas of government jobs and college admissions. It was opposed by other tribal groups, including those from the Kuki-Zo community.

But in the presentation, Assam Rifles officials pointed to policies of the chief minister that they believed fed the animosity between the communities. It noted Singh’s “hard stance” on the “war on drugs” and “vocal social media dissent”, among other things, for inflaming the conflict.

The presentation accused Singh of creating divisions between communities in the state’s campaign to stop drugs from being manufactured, traded and sold in Manipur. His forceful drive against the cultivation of poppies, grown in hilly regions of the state bordering Myanmar, drove home the impression that he is targeting Kukis.

The presentation also cited “state forces’ tacit support” of the violence and the “dismemberment of law-and-order machinery”.

Another factor in the conflict, the presentation noted, is “Meitei Revivalism”. Revivalism refers to the long history of the Meitei community aspiring to revert to its identity before the advent of Hinduism in the 18th century and later the merger of Manipur into India in 1949. The campaign led to a revival of Sanamahism in the 1930s and fuelled the armed movements subsequently.

The presentation lists Meitei Leepun and Arambai Tenggol, two Meitei organisations, as among the factors that has fuelled the conflict.

Arambai Tenggol was formed in 2020 “under the aegis of the titular king of Manipur and BJP Member of Parliament Leishemba Sanajaoba”, a police officer told me.

The Tenggol was initially formed as a sociocultural organisation focused on the revival of Sanamahi culture and later took up arms. It earned a more vigilante-like reputation in April last year after it broke into the house of a Meitei Christian pastor who had allegedly insulted the Sanamahism faith.

The Arambai Tenggol is helmed by Tyson Ngangbam, who goes by the pseudonym “Korounganba Khuman”. (Korounganba is a common Meitei name that means “sunshine” while Khuman is the name of a clan.)

TRC sent questions to Ngangbam through his social media account, which he has used during the conflict. The report will be updated if he responds.

In January, in a show of strength, Arambai Tenggol summoned 37 members of Manipur’s Legislative Assembly and two members of parliament from the state, including RK Ranjan Singh, the federal minister of state for external affairs and education, for a meeting at Kangla Fort, the palace of the Meitei kings in the heart of Imphal. It included lawmakers from the Meitei community across party lines.

Ngangbam spelled out the group’s demands, including updating the National Register of Citizens, a process by which the Indian government hopes to identify and exclude undocumented migrants.

The group also demanded abrogation of the Suspension of Operation – a peace agreement – with the Kuki-Zo armed groups, the relocation of refugees from Myanmar to the neighbouring state of Mizoram, border fencing along the Indo-Myanmar border, the withdrawal of the Assam Rifles from Manipur and the delisting of “illegal migrants” from the Scheduled Tribes list – a move that would exclude Kuki-Zo people from Myanmar from accessing the Indian government’s affirmative action policies. The lawmakers committed to back the demands.

Meitei Leepun, which is also of recent origin, is perceived as influenced by the ideology of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the fountainhead of a spectrum of hardline Hindu organisations, including the BJP. The leader of Meitei Leepun openly professes allegiance to the state’s chief minister and BJP leader Biren Singh, a Meitei.

Both Meitei Leepun and Arambai Tenggol face accusations from Kuki leaders of spearheading assaults by the Meitei community against their people. While Arambai Tenggol leans towards a stronger Meitei nationalist stance distinct from Hinduism, Meitei Leepun aligns with the Hindutva campaign led by the RSS and BJP.

A Meitei Leepun leader, Pramot Singh, told me: “We [the Meiteis] are followers of sanatana dharma. … If Meitei becomes extinct, the last outpost of sanatana dharma in Manipur is gone in the same manner Kashmiri Pandits are gone.”

Pramot Singh was referring to an upper-caste Brahmin group that lived in Kashmir but was forced to flee in the 1990s as they faced persecution and threats of violence by Kashmiri armed groups.

The Revivalists, in contrast, see Meiteis as distinct from the rest of India with their own cultural and religious identity and an erstwhile Manipuri kingdom called Kangleipak, which was merged by coercion into India in 1949.

The Assam Rifles presentation was silent on the political and business underpinnings of the conflict, the role of the federal government – under the BJP – and the Assam Rifles’ own failings and alleged bias.

According to the Assam Rifles presentation, the conflict is divided into three phases: “initiate”, “mutate” and “stalemate”. It laid out how the nature and character of the violence have changed through these stages.

My reporting over six months helped draw out details of what the paramilitary force’s presentation mentioned and what it left out.

The initiation

The embers of the current conflict – Biren Singh’s alleged political authoritarianism, hard stance on poppy cultivation, undocumented immigration, demand for Kukiland and Meitei Revivalism – have long smouldered.

But in April last year came the spark that ignited the simmering tension. This period was referred to by the Assam Rifles presentation as “initiate”.

That month, the Manipur High Court had asked the state government to consider petitions for including the Meitei community in the list of Scheduled Tribes – the constitutional provision that in the case of Manipur includes property ownership in the hilly areas dominated by Kukis. The Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reforms Act of 1960 allows only Scheduled Tribes to buy land in the hill areas.

Heeding a call by the All Tribal Students’ Union Manipur, the leading tribal civil society organisation in Manipur, for a “solidarity march” in the hill districts where tribal communities dominate, rallies were held on May 3 in Senapati, Ukhrul, Kangpokpi, Tamenglong, Churachandpur, Chandel and Tengnoupal.

As the march was winding up in the town of Churachandpur, news spread that a tyre had been set on fire in front of the Anglo-Kuki Centenary Gate, which was built to commemorate the 1917-1919 Kuki uprising against the British.

Subsequently, a group of young people approached the gate wielding weapons. Soon, word spread, suggesting that “militants” were provoking the crowd, Outlook magazine reported. Within a couple of hours, rumours spread through the state that Kuki mobs were vandalising Meitei houses.

The Assam Rifles officers’ presentation said the period of conflict starting May 3 was characterised by “high intensity riots”, “selective targeting” and it was “orchestrated and led by militias”.

Mobs ran amok in the towns, particularly in Imphal, located in the valley with a predominantly Meitei population.

“On the night of May 3 at 8pm, people wearing black shirts attacked us. We fired blanks, which forced them to retreat but just for some time,” said 43-year-old L Ngampao Khongsai, who had been living in Imphal’s Khongsai Veng area, a predominantly Kuki-Zo area.

According to Khongsai, a Kuki-Zo, the mob continued to attack the neighbourhood despite pushback from the security forces. “They would be saying that Kuki should be killed and threw stones.”

Khongsai fled with his family and hid at a nearby school. Like thousands of others from the valley, he ran and made his way to the Kuki-Zo-dominated Churachandpur district.

In the hill areas and closer to the foothills, mobs attacked Meitei neighbourhoods. A pregnant Warepam Rameshwori was forced to flee her village. “Our village is at the foothills in Tronglaobi Maning Leikai [in Bishnupur district] surrounded by Kuki villages. On May 3, the firing started. … [The Kukis] had sophisticated weapons and started firing at us, and we didn’t have any weapons to defend, so we ran away from there and found shelter at a relative’s home,” she said.

Seventy-nine Kuki-Zo and 18 Meitei individuals lost their lives from May 3 to May 23, according to an Assam Rifles estimate. This period also recorded a wave of attacks and looting of arms from police stations. According to the Assam Rifle assessment, 5,668 weapons were looted.

“[The state government] allowed the looting of arms. I mean, it is obvious because it is impossible for people to just enter the police stations and take out arms,” a retired police officer familiar with the security and intelligence operations in the region told me.

“So the Meitei civilians and the rebel groups had gotten weapons and started maintaining vigilance in the town. … In response, the other side felt that the SoO [Suspension of Operations] arms people should get out and distribute weapons amongst the Kukis,” he said.

The Suspension of Operations is the peace agreement signed among Kuki-Zo armed groups, the federal government and the Manipur government. The SoO requires Kuki-Zo militias to stay in designated camps and all their weapons be kept in the camp’s central armoury under the supervision of the state.

“The divide was complete, and that was the stage in the beginning when the political leadership should have cracked down very, very heavily,” the officer said.

That did not happen. The conflict spread and mutated, the Assam Rifles presentation noted.

More than 8,000 reports

TRC tried to redraw the initial period of the conflict by analysing 8,169 first information reports (FIRs) – 5,818 were filed in May and 2,351 in June.

An FIR is the first complaint filed either by citizens or police, which the police then have to investigate to determine whether a crime has been committed.

On May 3, an FIR was filed recording the initial trigger of the violence between the two communities. According to the FIR filed by the authorities: “A huge [number] of Kuki and Meitei youths numbering about 1,500 clashed among each other and vandalised and burned down many houses of both communities at Torbung Bangla. In that, many houses numbering about 300 houses and some private vehicles were also burnt down by the rioters. The police personnel fire[d] some rounds of tear gas smoke bombs and other ammunition to disperse the mob.”

The looting of weapons was reported as starting on May 4 with the first registered incident being reported at Manipur Police Training College in Imphal. According to the FIR, “The large mob overpowered the sentry and broke the lock of arm kote room and looted a large number of arms and ammunitions [sic],” including automatic rifles – 157 INSAS rifles, 54 SLR rifles and AK-47 rifles, among others. The looting of weapons continued until May 31, as recorded in these 8,169 FIRs.

In the first two months of the conflict, 7,831 cases of vandalism and incidents in which residents were forced to flee were reported. In addition, 189 cases of killings, assaults – including sexual assault – bodily harm and missing persons, and 79 cases of mass looting of weapons were also recorded.

Multiple FIRs were nearly identical or similar. For instance, on May 10, 76 FIRs filed in the Sagolmang police station in Imphal East District included a similar complaint: “Some unknown persons holding arms and deadly weapons numbering about 1,000 suspected to be Kuki Community from different villages entered at [name of place] and damaged the properties as well as burnt the house.” The only differences in the reports were the place names and the lists of damaged items.

A similar trend was seen in the police complaints filed by the opposing Kuki-Zo side.

“If a village with 40 households was burnt, there would be 40 complaints,” a second police officer said on the condition of anonymity. According to him, the “identical” cases were all combined to help the inquiry being led by a special investigative team.

The second phase

According to the Assam Rifles presentation, the character of the conflict began to change at the end of May.

This is the time when federal Home Minister Amit Shah made a four-day trip to Manipur to stitch up a truce. By then, the federal government, in an unprecedented move, had appointed a federal officer in charge of all security and policing operations in the state, bringing the state police and the federal paramilitary and army under one command.

The federal government may dismiss a state government and take over control of the state’s functions if it believes “the constitutional machinery” has failed. The constitution also requires the federal government to protect a “state against external aggression and internal disturbance”.

But in this case, the federal government kept its faith in the state government and did not invoke either of these constitutional provisions.

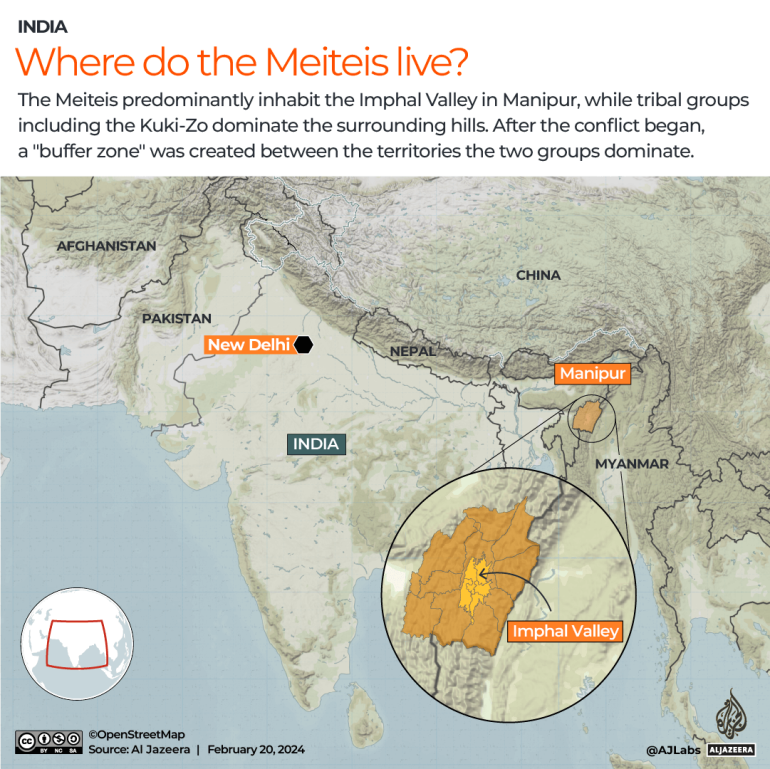

Again unprecedented, the government sought to achieve a truce by drawing up an ethnic boundary, calling it a buffer zone, dividing the Kuki-Zo from Meitei-dominated areas and enforcing this boundary through its armed forces.

Shah’s visit and the strategy to impose a unified federal policing command and the buffer zone failed.

The violence abated in the main Kuki-Zo or Meitei-dominated towns, but it shifted to rural areas. These rural areas, stretching from the Imphal Valley to the Kuki-dominated hills, are made up of small hamlets, villages and townships where Meitei and Kuki people have traditionally lived next to each other.

Now, the villages of both communities came under attack from armed groups on both sides. A battle to forcibly create ethnic territories had kicked off.

This phase stretched from May 23 to June 15.

On a September night, when I visited the Meitei village of Singda Kadangband, located at the edge of the Meitei-dominated Imphal West district, its residents spoke about the sleepless nights they had spent for the six months of the conflict.

About 170 men from 165 households had been taking round-the-clock shifts to stand guard at 10 bunkers set up on the periphery of the village.

In early June, the villagers were approached by Meitei fighters. “They came forward to help us, but we didn’t allow them. We are afraid that later they will take advantage of us,” said N Bobi Singh, who had been organising the surveillance.

This is when the Assam Rifles presentation acknowledged groups of fighters from both communities got involved.

The state has a long and troubled history with more than 30 armed groups from different ethnic communities that call it home. They have fought for demands that range from separate nation-states to the creation of new states within India based on ethnic identities.

Many of them draw resources from and camp in Myanmar. The influence of the Meitei armed groups, which were particularly targeted by the government’s armed forces, had been waning since the 2000s. And a majority of the Kuki-Zo armed groups had signed the SoO agreement with the government.

Researchers noted reports of how the Indian armed forces, with the help of Kuki militias, have strategically isolated militia factions from other ethnicities. This allegation, coupled with a track record of human rights violations and unlawful killings, has significantly tarnished the Assam Rifles’ standing within the Meitei community. The paramilitary is perceived as biased whereas the state police have faced accusations of bias against Kuki communities.

This conflict gave the Kuki and the Meitei armed groups a new lease on life, besides leading to the emergence of new Meitei militias.

On the Kuki-Zo side, the groups bound by the ceasefire had begun from the initial stages to help civilians who had taken up arms.

“Some of the [cadres] of the Suspension of Operations groups helped us set up the bunkers because they have experience,” said 35-year-old Mimin Sithlou, the joint secretary of the defence committee under the Committee on Tribal Unity, a conglomerate of civil society organisations functioning largely in Kangpokpi district, who oversaw the management of the bunkers there.

The involvement of these cadres put the “VBIGs under pressure” to also join the conflict to fight on behalf of the Meitei community, the Assam Rifles document noted. VBIGs are valley-based insurgent groups, referring to the older Meitei-affiliated armed groups.

They began “providing arms and ammunition”, consolidating their base and “increasing recruitment and ideological support”, the presentation said.

As militias on either side of the divide began amping up recruitment and training of young people, particularly from rural areas, the conflict would sometimes ebb but then pick up again. The stalemate came into being.

The stalemate

In Haipi village, located about 15km (10 miles) from the trenches dug at the border of Kangpokpi district, Christmas passed without any celebrations for Janggoulun Kipgen’s family.

I first met 19-year-old Kipgen in one of the bunkers in September. “We were trained for five to six days back in our village,” he told me, holding a rifle.

On December 25, sitting inside her house in Haipi, Kipgen’s mother, Neinkhongah Kipgen, told me: “Who won’t fear to send their son to the front lines? We can only pray that he’s safe.”

Meitei civilians in villages like Singda Kadangband also face a similar dilemma. The nights seem endless, and the days are spent with unceasing uncertainty.

“Except for the 60+-year-olds, everyone is expected to do 24-hour shifts,” a villager who didn’t wish to be named, told me back in September. “I have a one-year-old baby and work as a welder. I feel scared, but we don’t have much choice.”

“This will have a long-lasting impact, particularly on the young and future generations. They have guns to defend their community, but that is not exactly how it will pan out. The person might use it to solve personal enmity. Then some unemployed people might start extortion. Then there can be cases of mistaken identity killing and then revenge killing. It is going to become a vicious cycle,” retired Lieutenant General Konsam Himalay Singh told me.

What Lieutenant General Singh said had begun to play out by December when I last reported from Manipur. Videos of gun-toting men in the valley and the hills had proliferated on social media. The armed “volunteers” were being valorised on social media while in personal spaces, many spoke of the worries of young men being lured or recruited by militias, spawning a never-ending cycle of attack, revenge and turf war.

This is despite more than 60,000 armed personnel of the federal government’s paramilitary forces, the army and the state police enforcing a buffer zone dividing a large part of the state into two ethnic territories that each community fears crossing.

On April 19, Manipur will vote — along with several other parts of the country — even as the conflict rages on between the two communities.

“The chief minister should have been thrown out. He is the head of state, and if he can’t be trusted, … the army and police should have gone on overdrive and taken control over the area, … but eventually, it was allowed to continue because when it simmers, your voting aggregate increases,” said the retired police officer familiar with the security and intelligence operations in the region.

The second part of this series looks at the role of the drug trade, politics and armed groups in keeping Manipur on a boil.

Angana Chakrabarti is an associate member of The Reporters’ Collective.

(With inputs from Harshitha Manwani, Mohan Rajagopal, Aryan Chaudhary and Vedant Kottapalle)