Minister of Water and Sanitation Pemi Majodina; (DWS/X)

Water and Sanitation Minister Pemi Majodina says Gauteng's worsening water crisis is the result of local governments not cooperating with water conservation measures, allowing overconsumption and neglecting infrastructure.

Speaking to the parliamentary portfolio committee on water and sanitation on Tuesday night, she said what local authorities were experiencing was “self-inflicted suffering”.

Majodina said Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, particularly metro iThekwini, were battling increasing water outages, but “the whole of Gauteng is consuming too much water.”

Noting that the average global water consumption is 173 liters per person per day, Mr Majodina said: “In Gauteng it is as high as 290 liters, which is extraordinary and something needs to be done in Gauteng.'' We said it must be done.”

“We said there is a lot of unused water, a lot of non-revenue water. “And the only thing we can do to save Gauteng is to impose Level 1 restrictions. Gauteng must do the right thing.”

Since loose restrictions were imposed in September, no fewer than three meetings have been held to see if the situation has improved. “Unfortunately, I have to be honest: nothing has changed in terms of Gauteng doing the right thing,” Majodina said.

“We gave them four actionable things. One was for Gauteng to plug the leak immediately. This is doable. It can be done within the next 72 hours. Two. The eye is to disconnect the unauthorized connections. It is possible. We have said to Gauteng that we have to charge people in the right way. It is possible.

Gauteng is not in drought. “The disruption in Gauteng's water supply is due to demand outstripping supply, not due to a lack of water in the dams,” she said.

The state can change the situation “if there is political and management will” and Rand Water is “doing what is expected of it.”

She said the peak demand was caused by Gauteng “using more water than expected”. Rand Water extracts enough water to serve Gauteng province. ”

The minister said the ministry has set limits on the amount of raw water taken, and Rand Water is taking the maximum amount. Bulk water projects will only be able to extract additional water after the second phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project is completed in 2028.

The water crisis caused by population and economic growth in the country's economic heartland was anticipated by the ministry's planners in the 1980s.

“Non-revenue water for municipalities is also increasing,” Majodina said. “This includes illegal connections, unbilled connections, and even physical losses and leaks from city water systems.”

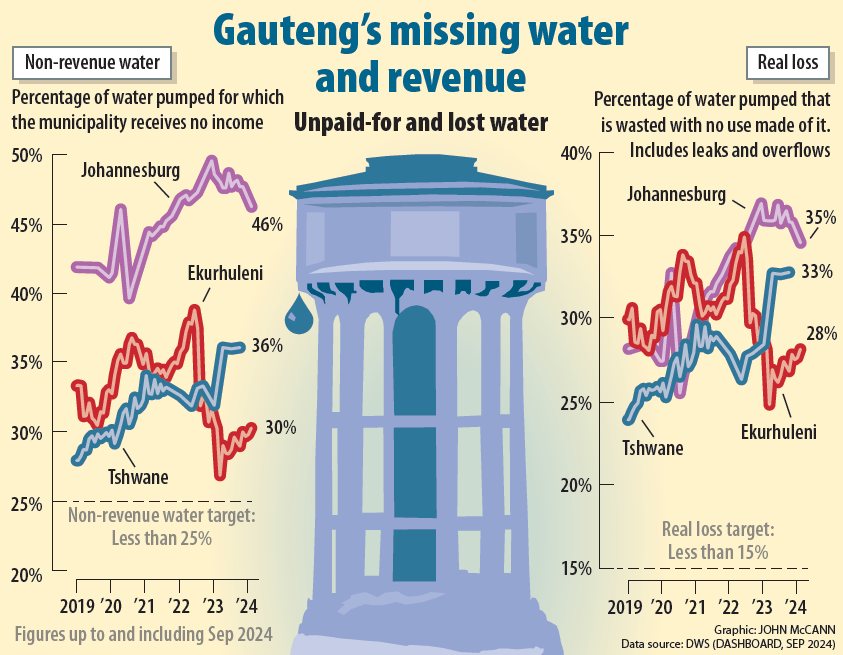

Non-revenue water is the amount of water that is pumped but for which the municipality does not receive any income. Although the target for South African municipalities is less than 25%, the actual loss of revenue is much higher: 46% in the City of Johannesburg, 30% in Ekurhuleni and 36% in Tshwane.

According to the Gauteng Water Safe Gauteng Department's dashboard, the number of leaks reported each year ranges from around 40,000 in Tshwane and Ekurhuleni to 100,000 in Johannesburg, with around 500 leaks every day in the Gauteng metro. has been reported. “Before a work order is completed, a back-office process is required to ensure that the work has been performed satisfactorily,” the document states.

Rand Water chief executive officer Saifo Mosai told the portfolio committee that the company has permission to pump 1.347 billion cubic meters of raw water from Vaal Dam. “As it stands, Rand Water is overdrawing water by 1.8 billion cubic meters per year.

“The ministry has given us temporary permission to abstract at this level, but in that permission it is clear that the ministry wants to reach a figure of 1.6 billion cubic meters per year,” he said. said.

“If anything, we should be talking about reducing the water we are already pumping from the Vaal Dam, which is part of the integrated Vaal River System.”

Mosai said he received a letter to that effect this week from department director Sean Phillips. “He said in his letter that due to delays in the Lesotho Highlands Water Project and climate change, only 1,600 cubic meters will be allowed to be mined between 2024 and 2028. The dam cannot be emptied.

The implementation of the second phase was postponed for nine years.

“When the Lesotho Plateau [Phase 2] Once it comes into effect, only 1.84 billion cubic meters should be taken annually. We have already exceeded that number from time to time,” Mosai pointed out.

This situation required collective leadership. “We have reached the limit of our provisional license. We are over-abstracting and, like other metros in South Africa and cities around the world, we have no choice but to implement water conservation and demand management measures.” he stated.

On average, Rand Water supplies 4.5 billion liters of water per day. “But what we've seen is an alarming trend that is still pushing up peak demand even in the winter. As we speak, we're doing 5,000 [to] 5,200 megalitres a day,” he said.

He added that too much water passing through a filter will clog it faster.

Non-revenue water rates in Gauteng remain close to 50%, while in Cape Town it is around 28%. “If people in the Western Cape can drink about 164 liters of water per person per day, we can do the same here in Gauteng.”

Rand Water's Chairman of the Board of Directors, Ramatheu Monicolo, said that Rand Water's main strategic risks are deterioration in the availability, reliability and quality of electricity, followed by pipelines, easements and property. said that it would be infringed. that drinking water supplies are unsustainable; Deterioration of the customer's financial health. delays in the implementation and completion of infrastructure projects; unpredictable weather patterns and extreme events;

Another risk is “a deterioration in Rand Water's own financial soundness due to excessive demand for non-revenue water, which reaches 49%, and its bankruptcy.'' [municipalities] The number of days it takes to pay off that debt is now approximately R7.8 billion.''Meanwhile, the number of days taken by debtors has increased from 35 days in 2014 to more than 100 days.

“Why does this law allow water boards to supply water to municipalities that do not pay their water bills?” Mosai asked. “Local governments will be paying their fair share of the cost of bulk purchases. They're always getting paid, but that money isn't going through them.”

He also raised the issue of water boards being closed. “When I came into the industry, we had 19 water boards, and we only have about nine left. Then we transfer the debt to another water board… It’s not legal to shut off the water completely. Not recognized.”

Rand Water's Monicolo said local governments are not taking matters into their own hands, but are instead using political leaders to put pressure on water utilities.

“We have held 46 meetings with municipalities, provinces, ministries and departments across Gauteng. The meeting addressed the issue of inadequate infrastructure in municipalities. It says there is no [and have] Insufficient storage space.

“We also raised the issue of leakages that exist there, non-revenue water that is increasing in municipalities, which is leading to fictitious demand, because we lose 49% of water; Because that demand is not the right demand.”

Mr Mosai said the top five defaulting or defaulting municipalities had a total of R3,832-billion in long-term arrears, including Emfuleni in Gauteng (R1.1-billion), Melafon (R980-million) ), Rand West City (R542 million) and Rand West City (R542 million). ).

Rand Water has debt relief programs in place for 10 municipalities, but only two municipalities, Tshwane and Mogale, are adhering to these agreements.

Companies that have not complied with payment arrangements include the Johannesburg Water Board and the City of Ekurhuleni.