When I was 16, I attempted to carjack two women who were walking to their cars in a dark parking lot, as well as a man who was asleep in his car. Because of the pain I caused these people, I was tried as an adult and sent to a state prison in Virginia. Going inside without a pistol, I was as defenseless as a child in such a place. So that hole was the safest place for me.

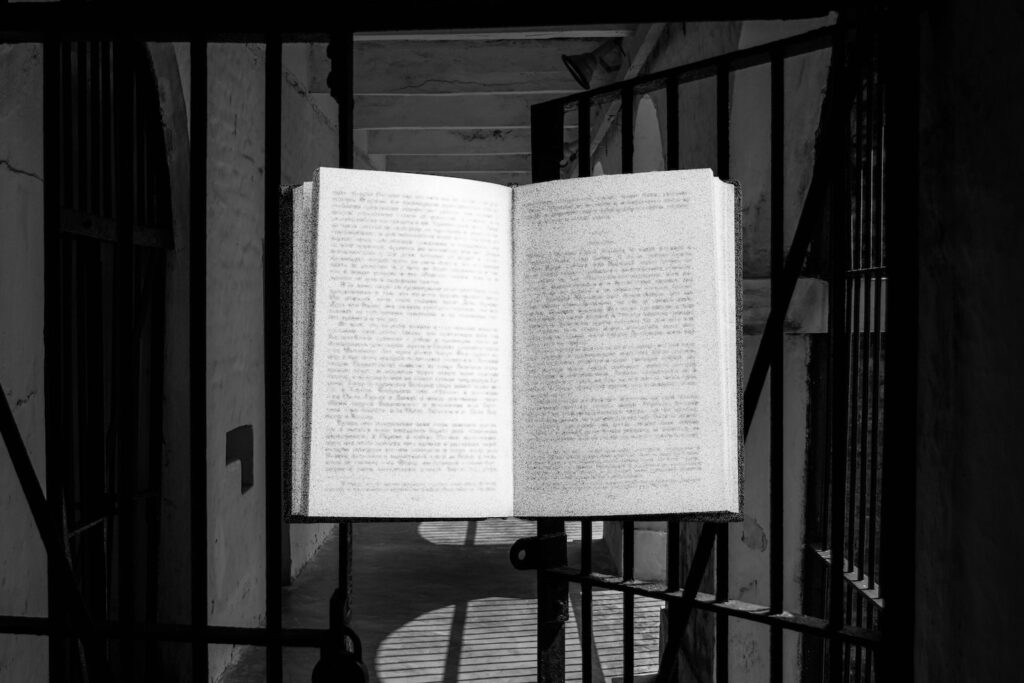

Each facility has its own code word for solitary confinement. hole. box. Shu. prison. All evoke fear. But I found solace in the hole. Every time I opened my eyes, a book was in my hand. Because the world of literature was the only thing that allowed her to imagine a future for herself beyond the capricious state control. It sustained me when everything else made me feel terribly alone, even the voices of men and boys around me.

There are contradictions in prison. The most alien world anyone can experience, it becomes the way we perceive suffering in the world. In February, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was found dead in his cell. The report about how he spent his last days reminded me of two things. Prison is the world's most universal method of torture, and books are central to the fight against post-prison disappearances.

Navalny spent about 300 days in solitary confinement. I spent nearly twice as much time inside her 7' x 10' cell in that hole. There was a time when beans were the only food available. A time when the air was cold and blankets were thin. And there was always a shortage of books.

“I spend most of the day with a book in my hand,” Navalny wrote. I first learned about Russian prisons from novels I picked up from prison recreation areas. The men in the novel were kept in nearly soundproof cages and created a code of knocks and taps. Around me, the men called handwritten notes “kites.” To alert their friends, they threw dental floss and nail clippers hundreds of feet from cell to cell.

If there is one thing that unites us in this world, it may be suffering. If that's true, then prison is a symbol of all the hurt in the world. And books are a symbol of letting go of hurt and becoming free.

There is a kind of insanity that comes from knowing that the prison is trying to kill you, knowing that the prison wants you to die, and yet insisting with all your being that you will live. There is a certain beauty in the belief that freedom may begin with a book.

While I was in the hole, the men devised an ingenious pulley system using lines made from torn sheets to shuttle books back and forth between the loners and the general population. A genuine library was transmitted along this system. One of her books introduced me to poetry, and then poetry introduced me to the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

In “Requiem,” Akhmatova writes about waiting 17 months at the gates of Leningrad prison for her son's release. A woman notices the famous poet and asks, “Could you please explain this to me?” She is a “mog,” Akhmatova wrote. “can.” Women Waiting in Front of Leningrad tells the story of every woman who has entered the visiting rooms of Virginia's Red Onion State Prison and Sussex 1 State Prison, and of every woman who has stood in front of prisons around the world. are sharing. These women are our conscience, telling us that we deserve better than a system that puts Franz Kafka's harshest tortures to shame.

In the days following her son's death, Lyudmila Navalnaya stood guard in front of the polar wolf colony. She requested her son's body to bury him. Her mother also went to prison for me. This is the shock that connects me to Mr. Navalny.

Books also connect me to Navalny. Between the pages of an encyclopedia, I discovered Mount Vesuvius, the Italian mountain I will be climbing with my mother this summer as an apology to her imprisoned mother. Books didn't bring Mr. Navalny to freedom, but they brought me to freedom. Could you please explain this? Women who love their sons in prison are waiting on the island. The people inside are also wondering as they are tied to a single sentence. Could you please explain this? Like Akhmatova, I would like to say the following. can. This is the fundamental potential of language in the face of human suffering.