A gatekeeper sits next to the flag of the National Labour Congress (NLC) at the entrance to the Federal High Court of Nigeria after labour unions launched an indefinite strike in Abuja on June 3, 2024. (Photo by KOLA SULAIMON/AFP via Getty Images)

This year alone, Moroccans have staged more than 100 protests over wages and living costs. From Agadir to Rabat, cleaners, engineers, medical workers and retirees have staged sit-ins to demand better and faster payment of wages and action to tackle soaring consumer prices.

“Everything is expensive and wages haven't changed much, except for teachers,” said Moroccan journalist Mohamed Acheari.

After a four-month delay, the Ministry of Education in April began paying part of a $140-a-month salary increase agreed with Morocco's teachers union.

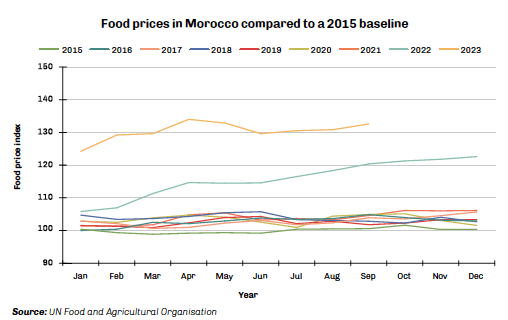

The past six years have seen a prolonged period of bread protests, with food price inflation so high it peaked at 32% in February 2023.

Concerns over food, prices and wages have sparked at least 916 protests since 2019, an average of 15 per month, an unusual number for the country, which had seen just seven such protests in the three years prior to this period. Acheari said this was the new “normal” given the economic situation.

Broader concerns

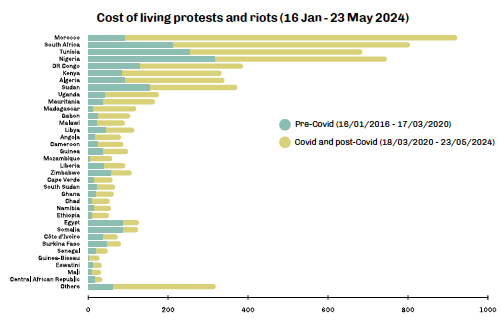

Rising living costs have also put governments in at least 12 other African countries under pressure from their citizens in recent years.

In Kenya, protests have doubled in 2020 compared to the two previous years. Authorities in South Africa, Tunisia, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Algeria, Sudan and Uganda are also under similar pressure.

A study of nearly 59,000 reports of protests in Africa collected by the Armed Conflict Locations Data Project between January 16, 2016 and May 23 this year found that 7,164 protests were sparked by concerns about food, wages (wages and salaries) and prices.

Most were peaceful protests, such as sit-ins organized by labor unions, but 13 percent turned into riots, with protesters blocking roads, burning tires, looting food from government warehouses, and attacking food and agricultural traders.

Most of the protests have taken place in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: 5,039 protests have taken place since March 18, 2020, when a global pandemic was officially declared, compared with 2,125 protests in the same period prior to that.

Protests across the continent over the rising cost of living have more than doubled since the pandemic began, but COVID-19 is not the only problem.

Morocco's crisis was brought about by a shift in agricultural policy, with the country growing agricultural production to $12 billion a year under an ambitious plan called the Green Morocco Plan.

But as agriculture became more successful, authorities began encouraging farmers to grow export crops, especially vegetables. Eventually, traders were selling their fresh produce in Morocco for roughly the same price they would get if they sent it to Europe. The minimum wage in Morocco is just 275 euros (about R5,580), well below Portugal's 956 euros and Spain's 1,323 euros.

Protests have broken out across the country, calling on the government to prioritise “food sovereignty” over exports – sentiments that are likely to grow as harvests shrink due to drought caused by climate change.

In Nigeria, where strikes shut down the national electricity grid last week, the pressures, which have been building since at least 2016, have a lot to do with stagnant wages, exacerbated by record-breaking inflation (33 percent, the highest in 28 years).

The current minimum wage is 30,000 naira (roughly R358) a month, but unionists say 494,000 naira ($318) would be a better option. In negotiations with unions in Abuja, the government has offered 60,000 naira ($40).

Economics professor Stephen Onyeiwu wrote in The Conversation that this is not enough to lift workers out of poverty: “The number of poor in Nigeria has been increasing for the past eight years, and this trend will continue until the minimum wage reflects the cost of living and recognises the importance of social services such as health, education and housing.”

He said if it had been based solely on foreign exchange rates, it would be worth 265,000 naira ($170) now.

This article was first Continenta weekly newspaper distributed across Africa. Mail & GuardianDesigned to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Download the free version. here