Since South Africa adopted a post-apartheid constitution in 1996, it has made significant progress in realizing social security rights and reducing poverty and inequality.

Policies, laws, and administrative infrastructure enabled the government to create an extensive social security system. Two out of three households receive social subsidies, and 60% of the workforce is covered by social insurance.

South Africa now exemplifies an upper-middle-income country that is ahead of many other countries in expanding social protection to foster development.

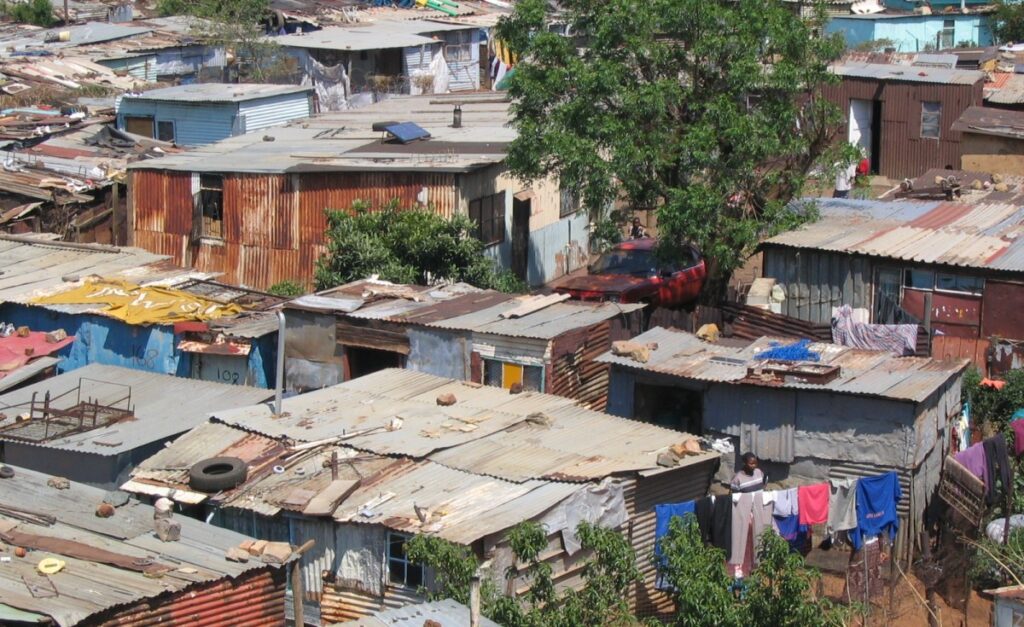

Despite this, the country continues to have exceptionally high levels of poverty, unemployment, inequality, and low levels of economic growth.

As South Africa commemorates Human Rights Day on 21 March, it is worth reflecting on what has been achieved, what policies and interventions are needed, and what the future holds.

what's in it

Social security consists of several pillars. One of them is social assistance. This is paid by the state to various categories of vulnerable people, including the elderly, physically and mentally disabled, children and their families.

Net assistance has grown from 3 million people in 1995 to more than 18 million people in 2022.

The second pillar is social insurance. This takes the form of employment-related contribution schemes, such as unemployment benefits, health benefits and pension benefits. The provision of informal social and family support also plays an important role.

Some other interventions are not generally classified as part of a country's social security system. These include a social package of public employment schemes, school meals and free basic services. Free primary health care, free education for poor children, and subsidies to NGOs that provide early childhood development centers and welfare services also fall into this category.

Recently, a new temporary Social Distress Relief Grant was implemented to help alleviate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of beneficiaries of this scheme has increased from 5.3 million in 2020 to 10 million in 2022. This system targets unemployed people and non-regular workers who are unable to support themselves.

It is clear that social assistance is the basis of this country's social security system. The organization operates with a shoestring budget for social services such as community mental health, substance abuse and gender-based violence, among others. Human services have historically been underfunded and this trend continues.

However, the social security system has some problems.

Importantly, while most poor people are unemployed or employed in precarious, low-wage jobs or the informal sector, this policy does not adequately address or respond to unemployment. about it.

Additionally, the system is poorly coordinated. There are weak connections between different programs. For example, caregivers receiving child support subsidies do not have immediate access to other services such as social and nutritional support, public employment, and early childhood education. This undermines the system's structural efficiency, effectiveness, and responsiveness to meet diverse needs throughout the lifecycle.

Policy gaps and interventions

The role of social assistance is now widely accepted as a cornerstone of national efforts to accelerate poverty reduction and income redistribution. The question is how best to accomplish this.

Several high-level policy solutions emerged from the policy review I recently conducted for a new book.

First, there is a need for social security reform that focuses on closing disparities. These include support for the long-term unemployed, the chronically unemployed and irregular workers.

Second, to address malnutrition more effectively, we need to increase the level of social subsidies, especially the child benefit subsidy. Current subsidy amounts are below the food poverty line.

Innovative supports are also needed to improve participation for the large number of children who are eligible but do not receive subsidies. These are estimated to be 17.5% of eligible children.

It also states that social assistance alone will have limited effectiveness in lifting people out of poverty and improving income mobility unless employment is expanded through a range of public and private measures and such work is sustainable. Awareness is also spreading. Increased employment and improved quality of work will lead to more people joining the social insurance system, creating a larger middle class.

The social and economic challenges intensified by the pandemic are likely to continue. This could further deepen structural unemployment and cause some jobs to be permanently lost. Continuous monitoring of economic recovery and social development indicators over time can aid in more effective policy-making.

Social policy solutions are needed to extend interim social relief in the short to medium term. They also need to address systemic improvements to overcome delivery challenges. South Africa may do well to follow other countries in Latin America, such as Indonesia and Mauritius, which maintain social registers. These allow authorities to identify potential beneficiaries in need and assist with planning. This also increases the responsiveness of social support.

The temporary expansion of social assistance due to the pandemic poses new challenges. As the economy begins to recover and jobs are created, thorny political issues could arise if COVID-19 relief subsidies are cut or phased out. There is potential for significant political instability. This is because the social and humanitarian crises that the grants were intended to alleviate will continue.

Therefore, it is highly likely that the COVID-19 hardship relief subsidy will become a basic income subsidy by default. It is not clear what form this will take, but the government has announced that it is considering its options.

Questions remain about how affordable these policy options are. Cost-benefit analysis will be required to support policy initiatives and decision-making. The costs and consequences will depend on whether basic income subsidies prioritize those who need them most or are given to all income groups.

Given the country's fiscal constraints, consideration should be given to the fact that further expansion of income support is likely to crowd out other social policies and social development programmes.

As well as increasing cash transfers at the expense of non-monetary forms of social provision, including health and mental health services, education, early childhood education, social welfare services, and basic services such as housing, water, sanitation, and electricity. It may have the opposite effect.

Carefully designed, innovative, evidence-based complementary interventions are needed. These must build human capital and human agency, strengthen families and improve community-level livelihoods. Like other similar interventions, these should ultimately aim to break intergenerational cycles of disadvantage.

Leila Patel, Professor of Social Development, University of Johannesburg