Like other parts of the world, South Africa has imposed restrictions on social movement and interaction to curb the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a We implemented a national lockdown for five weeks, followed by risk adjustment. , phased economic reopening. However, such lockdown policies always result in significant welfare losses for individuals and households. Pandemic-related shocks to employment, working hours and incomes for low-wage and vulnerable workers have exacerbated South Africa's already high levels of poverty and inequality. With these welfare losses in mind, President Cyril Ramaphosa last month announced the government's Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan (ERRP) to recover South Africa's economy after the devastation caused by the pandemic.

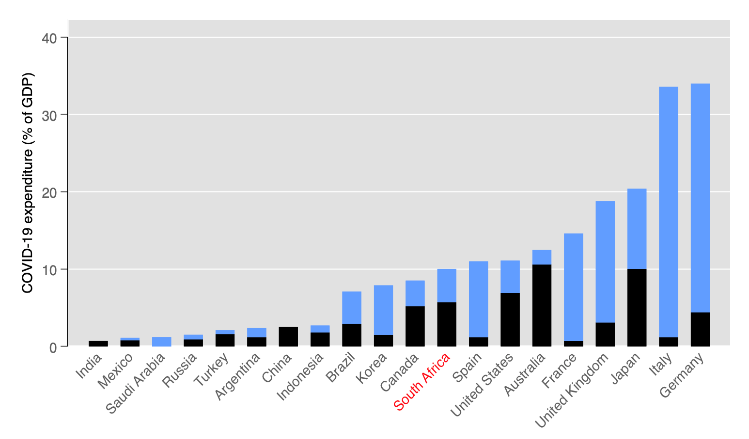

Ramaphosa's coronavirus stimulus package, originally announced on April 21, is huge, amounting to about $26 billion, equivalent to 10% of the economy's GDP (Figure 1). As a share of GDP, South Africa's policies are the largest in emerging markets. significantly larger than some high-income countries, including South Korea and Canada. South Africa is spending huge sums of money to rebuild the country, even if we only look at government spending that is 'above the line'.

Figure 1. Spending on COVID-19 countermeasures by country (% of GDP)

Source: Bhorat et al. (2020). Author's own calculations.

Around 90 per cent of the stimulus package will include additional medical support, support for municipalities providing basic services, wage protection through the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF), further income support through the tax system, small and medium-sized enterprises and informal enterprises. Allotted financial support to. , and the biggest component is the credit guarantee system.

Notably, approximately 10 percent of the stimulus package, or $3.2 billion, was allocated to social assistance, including both intensive (increasing the amount of all existing social subsidies) and broad-based measures. (A new, special COVID-19 social relief grant has been introduced for the six-month period from May to October 2020.) It is aimed at individuals who have no income or receive any other social grants or support from the UIF. It also included further extending the availability of COVID-19 grants, which reached a remarkable 4.2 million people previously unreachable (equivalent to 4.2 million people previously unreached), and which subsequently included a further extension of the availability of the COVID-19 grant.Poverty reduction effects. , previous research has shown that the distribution of COVID-19 subsidies is relatively pro-poor: for each subsidy recipient in the richest household quintile, and five or more other recipients live in the poorest household.

Table 1. Changes in social assistance in South Africa due to COVID-19 (by type of subsidy)

Source: NIDS (2017), GHS (2018), and Ministry of Social Development (2020). Author's own calculations.

Note: *COVID-19 grant eligibility and prerequisites are discussed in Bhorat, Oosthuizen, Stanwix, 2020..

As of mid-October, 18.5 million COVID-19 grants had been distributed to 6 million unique individuals, resulting from more than 9 million applications since May. Considering the eligibility criteria for the COVID-19 subsidy and some prerequisites for recruitment, we estimate that the subsidy could reach up to 10 million people. Combined with the existing child benefit subsidy, which has already reached 13 million children and 8 million caregivers, and other subsidies that have already reached around 5 million recipients, President Ramaphosa's package will , could provide much-needed support to around 36 million people, or 61 percent of the country's population. Population of South Africa. The widespread reach of the social assistance system, which covers just under two-thirds of the country's population, is commendable.

After all, the South African government's stimulus package is large by global standards, and its scope in terms of support for the poor and vulnerable is impressive. The credit guarantee system, which makes up two-fifths of the economic stimulus package, requires the private banking system to lend to companies in financial distress. This is a key element of the stimulus package, which links government support to the private sector through banks, but implementation has been slow and subject to strict credit standards for South Africa's financial institutions. Furthermore, this support comes at the expense of a significant increase in the budget deficit. Further stimulus is likely to prove fiscally unsustainable. The challenge for governments and policymakers now shifts to finding ways to put the country on a prudent and optimal path to fiscal consolidation, both in terms of revenue collection and expenditure.

read more

Baskaran, G., Bhorat, H., and Köhler, T. (2020). South Africa’s COVID-19 special grants: A brief assessment of coverage and expenditure dynamics. DPRU PB 2020/55. Development Policy Research Unit Policy Brief, November 2020. University of Cape Town.

Bhorat, H., Oosthuizen, M., and Stanwix, B. (2020). Social assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa: An impact assessment. Development Policy Research Unit Working Report 202006. DPRU, University of Cape Town.

Köhler, T., and Borat, H. (2020). COVID-19, social protection and the labor market in South Africa: Are social grants targeted to the most vulnerable? Development Policy Research Unit Working Paper 202008. DPRU, University of Cape Town.

Bhorat, H., and Köhler, T. (2020). Social assistance during South Africa's national lockdown: COVID-19 subsidy, changes to child support subsidy and consideration of policy options from October onwards. Development Policy Research Unit Working Report 202009. DPRU, University of Cape Town.